Assessment of Learning Disabilities

Assessment of Learning Disabilities:

Cooperation between Teachers, Psychologists and Parents

_____ African edition _____

Edited by Tuija Aro and Timo Ahonen

Cooperation between Teachers, Psychologists and Parents

____ African edition ____

Edited by Tuija Aro and Timo Ahonen

This African edition is based on the original publication by Mika Paananen, Tuija Aro,

Nina Kultti-Lavikainen & Timo Ahonen (2005). Oppimisvaikeuksien arviointi: Psykologin,

vanhempien ja opettajien yhteistyönä. Finland: Niilo Mäki Institute ©

Translation of the original Finnish text: Molehill Communications / Aki Myyrä

Proofreading of the African edition: Kalle Rademacker

Editorial team: Pia Krimark, Niilo Mäki Foundation, Lusaka, Zambia and Susanna Kharroubi,

University of Turku, Finland

Photography: Mr. Mumba E. Mwaba, Timeslice World, Zambia

Layout: Mirja Sarlin, University of Turku, Finland

Printed by: Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy – Uniprint (2011)

This book is published in collaboration with University of Turku, Finland and

Niilo Mäki Institute, Jyväskylä Finland.

1. edition 2011

ISBN: 978-951-29-4687-7 (painettu)

ISBN: 978-951-29-4688-4 (verkko)

Contributors

Ahonen, Timo, PhD

Professor of Developmental Psychology

Department of Psychology

University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Aro, Mikko, PhD

Professor of Special Education

Department of Educational Sciences

University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Aro, Tuija, PhD

Senior researcher

Niilo Mäki Institute Jyväskylä, Finland and

Senior lecturer

Department of Psychology

University of Jyväskylä, Finland

February, Pamela, M.Phil

Senior Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology and

Inclusive Education

University of Namibia, Namibia

Haihambo, Cynthy Kaliinasho, PhD

Senior Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology and

Inclusive Education

University of Namibia

Hengari, Job Uazembua, M.Phil

Senior Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology and

Inclusive Education

University of Namibia, Namibia

Imasiku, Mwiya. L., PhD

Head of Department

Department of Psychology

University of Zambia, Zambia

Kwena, Jacinta, PhD

Senior Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology

Kenyatta University, Kenya

Matafwali, Beatrice, PhD

Head of Department/Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology,

Sociology and Special Education

University of Zambia, Zambia

Miyanji, Osman, Dr

Childneurologist/Consultant

Gertrude´s Children Hospital

Nairobi, Kenya

Mkandawire, Lomazala, B.Ed

Senior Lecturer

Department of the Education for the Children

with Learning Disabilities

Zambia Institute of Special Education, Zambia

Muindi, Daniel, PhD

Senior Lecturer

School of Education

Kenyatta University, Kenya

Munsaka, Ecloss, PhD

Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology,

Sociology and Special Education

University of Zambia, Zambia

Möwes, Andrew Dietrich, PhD

Senior Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology and

Inclusive Education

University of Namibia, Namibia

Jere-Folotiya, Jacqueline, MA

Lecturer

Department of Psychology

University of Zambia, Zambia

Kachenga, Grace Mulenga, M.Sc.

Principal

Zambia Institute of Special Education, Zambia

Kalima, Kalima, M.Ed

Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology,

Sociology and Special Education

University of Zambia, Zambia

Kariuki, David, MA

Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology

Kenyatta University, Kenya

Kasonde-Ngandu, Sophie, PhD

Senior lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology,

Sociology and Special Education

University of Zambia, Zambia

Kharroubi, Susanna, MSc

Project manager

University of Turku, Finland

Koponen, Tuire, PhD

Senior researcher

Niilo Mäki Institute

Jyväskylä, Finland

Kultti-Lavikainen, Nina, Psych. Lic.

Clinical Psychologist

Niilo Mäki Institute

Jyväskylä, Finland

Mwaba, Sydney, PhD

Senior Lecturer

Department of Psychology

University of Zambia, Zambia

Namangala, Phanwell H., MA

Lecturer

Department of Psychology

University of Zambia, Zambia

Ndalamei, Inonge Mwauluka, B.Ed

Senior Lecturer

Department for the Visually Impaired

Zambia Institute of Special Education,

Zambia

Ndambuki, Philomena, PhD

Senior Lecturer

Department of Educational Psychology

Kenyatta University, Kenya

Otieno, Suzanne Adhiambo, MA

Niilo Mäki Institute

Jyväskylä, Finland

Paananen, Mika, Psych. Lic.

Clinical Neurosychologist

Niilo Mäki Institute

Jyväskylä, Finland

Phiri, Gawani Douglas, B.Ed

Senior Lecturer

Department for the Hearing Impaired

Zambia Institute of Special Education,

Zambia

Foreword

Timo Ahonen, Tuija Aro and Susanna Kharroubi

In every class there are probably some children with learning difficulties. Perhaps the child cannot learn to read fluently or may not be able to learn multiplication tables by heart. He or she may be slow at mental calculation or finds learning new motor skills problematic – there are many types of difficulties. During their career, every teacher meets several children for whom learning is laborious and even children who think that they cannot learn. Teaching these children is a challenge for the instructor. In fact, it is a challenge for the entire school. This book was written for teachers, educational or school psychologists and parents to guide them in helping children to overcome the challenges of learning difficulties.

Education for the Children with Learning Disabilities: African-European Co-operation for Promoting Higher Education and Research project was a joint action between Psykonet – University Network in Psychology from Finland coordinated by the University of Turku; University of Namibia Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education; University of Zambia Department of Psychology; University of Zambia Department of Educational Psychology, Sociology and Special Education; Zambia Institute of Special Education; Kenyatta University Department of Educational Psychology; and Niilo Mäki Institute (Finland). The project aimed at enhancing the curricula of the African partner institutions in the field of learning disabilities among school children.

This book is an outcome of three years of systematic and successful work between the project partners. This publication which is considered a “training standard” forms together with the Guidelines on Learning Disabilities and the Instructions for Local Authorities (published in 2011 in the newsletter Learning and Learning Disabilities in Africa) an integral part of the partner institutions´ curricula on learning disabilities.

The book was written by a multiprofessional and multicultural group of experts on learning disabilities, and it combines the best practices from Finland, Kenya, Namibia and Zambia. The concept of learning disabilities is relatively new in Africa although the phenomenon of children with learning difficulties or those described as “slow learners” is not (Abosi, O. 2007). There is no particular definition of learning disability that one can refer to as “the African definition”. The term refers to children who experience learning difficulties independent of obvious physical defects such as sensory disorders. It is understood that children with learning difficulties have the ability to learn but that it takes them a longer time to comprehend things than the average child (Abosi, O. 2007). Also, African experts base their concept of learning disabilities on Western definitions such as follows:

Learning disability – is a general term that refers to a heterogeneous group of disorders manifested by significant difficulty in the acquisition and use of listening, speaking, reading, writing, reasoning, or mathematical abilities. These disorders are intrinsic to the individual, presumed to be due to central nervous system dysfunction, and may occur across the life span. Problems of self-regulatory behaviour, social perception and social interaction may exist with learning disabilities, but do not by themselves constitute a learning disability. Although learning disabilities may occur concomitantly with other handicapping conditions (for example sensory impairment, mental retardation, social and emotional disturbance) or with extrinsic influences (such as cultural differences, insufficient or inappropriate instruction), they are not the results of these conditions or influences (National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities, NJCLD, 1988, 1993).

Similarly Hammill (1990) has put the concept of learning disability (LD) into a nutshell as follows:

LD is marked by heterogeneity, LD is probably the result of CNS dysfunction, LD involves psychological process disorders, LD is associated with underachievement, LD can be manifested in spoken language, academic or thinking disorders, LD occurs across the life span, and LD does not result from other conditions.

When problems with learning are first observed, an attempt is made to uncover their causes and source, which are often uncertain. In Finland, parents and teachers can usually obtain help from the school psychologist in uncovering the causes of problems, as well as from health and social services personnel. There are established practices and evaluation methods for assessing learning difficulties. How the information gathered with various methods can be utilised to promote the child’s learning is a challenge for the teachers, school psychologist, and also the health and social service workers. In African countries, the evolution of school psychology services closely follows a developmental pattern: First priority is given to the widespread provision of general education services that precede the special education services and school or educational psychology services. This means that many countries of sub-Saharan Africa are still lacking these services, especially in rural areas, despite communities, schools, and students having needs that can be met by school psychology services. These needs include educational support (the focus of this book) as well as stress and health management in view of the pressures on children and their families due to industrialisation, poverty and disease (Mpofu, Peltzer, Shumba, Serpell, & Mogaji, 2005).

The first part of this book briefly describes what efficient learning requires from the school, class, family and child. “Learning disability” is defined and a line is drawn between learning disabilities and school difficulties resulting from other causes such as inadequate school management, lack of well-trained and effective teachers in the schools, large class sizes, providing early primary education in an international language that is not the child’s mother tongue, lack of teaching materials, and unfortunately – still – sometimes negative attitudes among some teachers toward children with disabilities and their inclusion in regular schools as a result of teachers’ traditions and culture, as described by Abosi (2007).

The second part presents a four-step assessment model for learning disabilities, which emphasises cooperation between the school, the family, and the school or educational psychologist. The third part of the book describes difficulties in academic skills and cognitive functions, and their assessment. The development and sub-processes of each skill and function are described in detail to facilitate assessment. We are painfully aware that there is still a huge amount of work to do in developing adequate and culturally acceptable assessment tools for teachers and psychologists in African countries working with children who have learning disabilities (see Grigorenko, 2009) We really hope that this book will stimulate these efforts. The final part summarises the theoretical discussion of the earlier parts of the book and introduces the interpretation of assessment results. It also shows how conclusions can be made based on the results, and how support can be planned for the school, class and home.

The book is meant for teachers, special education teachers, and psychologists who perform learning disability assessments, as well as for therapists in various fields. It offers basic information about learning disability assessment, the relationship between academic skills and cognitive functions and the development of these skills, as well as the significance of their development for learning.

We wish to thank numerous professionals who have contributed to this book with their valuable comments in Finland, Kenya, Namibia and Zambia. Our special gratitude goes to the University of Turku for coordinating the project, and the University of Jyväskylä and the Niilo Mäki Foundation for their active role in the project planning an implementation.

References

Abosi, O. (2007). Educating children with learning disabilities in Africa. Learning Disabilities

Research & Practice, 22, 196–201.

Grigorenko, E.L. (Ed.)(2009). Multicultural Psychoeducational Assessment. New York: Springer

Publishing Company.

Hammill, D.D. (1990). On Defining Learning Disabilities: An Emerging Consensus. Journal of

Learning Disabilities, 23, 74–84.

Mpofu, E., Peltzer, K., Shumba, A., Serpell, R., & Mogaji, A. (2005). School psychology in

sub-Saharan Africa: results and implications of a six-country survey. In C.L. Frisby & C.R.

Reynolds (Eds.), Multicultural School Psychology (pp. 1128–1150). Hoboken NJ: John

Wiley & Sons.

Tuija Aro, Jacqueline Jere-Folotiya, Job Hengari, David Kariuki and

Lomazala Mkandawire

1. Learning and learning disabilities

What factors at school and in educational environments affect a child’s learning?

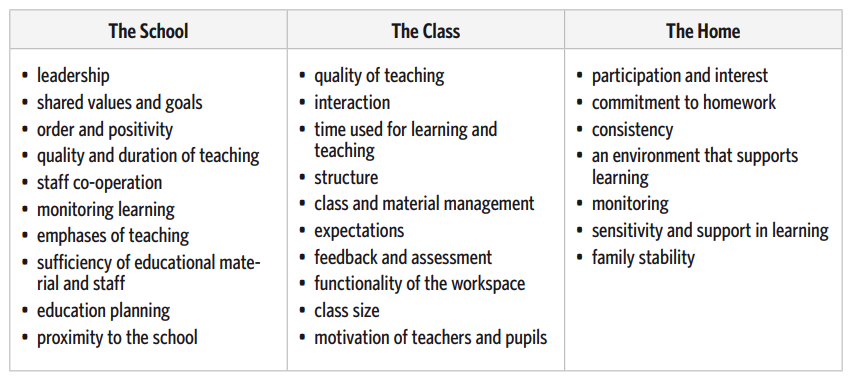

School learning is affected by many factors. The personal characteristics of the child, familial attributes, and factors related to the school and class altogether affect the child’s ability and potential to benefit from teaching. These factors influence the child’s learning experiences and in the process affect the child’s self-image as a learner, among many other attributes. These experiences, the child’s beliefs, and his/her knowledge and skills, together with the characteristics of the environment, form a complex interactional system. Understanding this system helps us to understand the underlying factors in children’s learning difficulties which is a prerequisite for planning and implementing effective pedagogical and intervention strategies. Scientific research on school learning has examined various school factors, which include school systems, and schools’ organisational structures and curricula (see e.g., Wang et al., 1994). Some of this research has focused on factors pertaining more directly to the child, such as the child’s characteristics and the teaching methods used in the school. These studies reveal that child-related factors, as well as family and close community-related factors, are central to the effectiveness of learning. However, we must not focus merely on the child and his/ her skills or lack of skills as we examine problems with learning. We must perceive the child as a part of his/her environment, understanding that today’s difficulties may spring from the child’s early experiences and familial factors in addition to the impact of diverse environmental variables, cultural customs, and other unique local structures. All these factors are discussed in detail in the following sections.

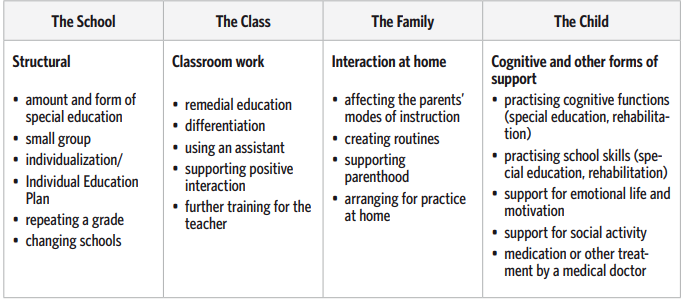

Table 1. Factors within the child’s various environments that affect learning (following Christenon &

Ysseldyke, 1989; Reynolds, 1997)

Box 1. Finland – An example of a success story in basic education

Based on different international comparative studies, we know that the Finnish school system has been

very successful:

- The IEA Study in 1991 (International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement): Finnish student , aged 9 and 14 years, were found to be the best readers in the Reading Literacy category

- The IALS in 1998 (International Adult Literacy Survey): Finnish young adults, aged 16 to 25 years, also outperformed their peers in other countries.

The same conclusions have been drawn by the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) studies in 2000, 2003 and 2006. More specifically, in 2000, a total of 265,000 fifteen-year-old students from 32 countries took part in the PISA study. The PISA assessed literacy in three domains: Reading, Mathematics and Science. The PISA assessed particularly young people’s capacity to use their knowledge and skills in order to meet real-life challenges, rather than merely looking at how well they had mastered a specific school curriculum. Reading literacy is a key competence in today’s society because it contributes to an individual’s mental growth, learning, work and active citizenship. Reading literacy is based on basic technical reading as well as on a broader conception of reading where stress is laid on the construction of meaning from the text. It is very interesting that the average literacy level of a nation’s population is an even better predictor of economic growth than its overall educational level. The PISA studies show that the Finnish educational system has succeeded not only academically, but also in promoting relatively high equality among 15–year-olds. Finnish students showed the highest achievement (in 2006 the second highest) in reading literacy. The number of poor readers has been remarkably low in Finland, and the gap between low and high achievements relatively narrow.

Factors behind the high Finnish educational scores in the PISA

- Finnish boys are good readers, but Finnish girls are even much better than Finnish boys.

- Even the lowest-performing Finnish schools are very good compared to the OECD’s average, possibly due to more equal opportunities for learning.

- Finland’s lowest-scoring students perform better than their comparative students in other OECD countries (including in mathematical and scientific literacy).

- The difference between top performers was much less pronounced.

- The positive effect of the Finnish strategy of supporting students from disadvantaged back grounds and with learning disabilities could be seen in the results of the PISA studies in 2000, 2003 and 2006. The impact of parent’s socioeconomic status on students’ performance was relatively low.

- Finnish students’ engagement in reading is very high, especially among the girls positive attitudes toward reading, frequency of reading diversity of reading material.

General background of Finland’s educational success

- The high quality and comparatively high equality of basic education is grounded in a publicly funded system of education that is comprehensive and non-selective.

- Schools are open to all children, irrespective of their gender, place of residence, language, or socioeconomic background.

- The effort to minimise low achievement and boost inclusion has proved successful. Minimal between-school variation is one of the key factors associated with high performance.

- There is no connection between a school’s status and the average performance of its students. It seems to make little difference, where a student lives or which school he or she attends – opportunities to learn are the same, but male gender and immigrant background seem to increase the risk of low-achievement also in Finland.

- Pedagogical philosophy and practice: The school is there for every child and the school must adjust to the needs of each child, not the other way around.

- Reasonable class size (on average 19 students per class in grade 9, in 2003) and support, as well as part-time special education (received on average by 20 % of students during their nine years of schooling) for children with learning disabilities are offered.

- Student welfare groups are active in the schools (consisting of teachers, principals, counsellors, psychologists, school nurses and doctors).

- Well-educated teachers abound since all teachers, even those teaching primary grades, have a master’s degree (MA) either in Educational Science or, if different, in their respective field of teaching. Teachers also have considerable pedagogical autonomy in the classroom in respect to organising their work within the flexible limits of the national curriculum’s framework.

Conclusion

There is no single secret or key behind the success of the Finnish educational system. High performance is related to cultural factors, the educational system, curriculum, pedagogical and assessment practices, and to individual characteristics of the students and their families.

Read more:

Linnankylä, P. & Arffman, I (Eds.) (2007). Finnish Reading Literacy. When quality and equity meet. University of Jyväskylä: Institute for Educational Research.

The school as a factor

In all communities, the school is considered as an important decision maker and implementer of teaching and support for learning. An effective teacher is one who is proficient in planning and implementing teaching programmes in addition to making sound decisions regarding remedial strategies geared towards catering for individual differences among learners. In many African countries, the curriculums are rather rigid and the teachers are compelled to follow the syllabus that has been laid down. In the African context, as in Zambia, Namibia and Kenya, the schools follow a basic curriculum formulated by the respective Ministries of Education. For each grade level, a syllabus is available based on the curriculum, and from that syllabus teachers are expected to formulate their teaching plans using the teaching schemes as well as the teachers’ guides and pupils’ text books. In Finland, teachers have more freedom to plan their teaching. This trust in teachers’ professional competence is based on the high quality of the teacher training at the master’s degree (MA) level.

The support that the child and his/her family receives from the school, as well as the cooperation between the home and the school, is essential for the assessment of learning disabilities and the implementation of intervention strategies. Cooperation among students, parents, the school and the community in general is vital for the well-being of the student. Moreover, the support of the heads of school for the teacher helps both parties to develop good practices and inspires a belief in the significance of their respective roles at the school and its organisation. Accordingly, advice and instructions from such key figures can be helpful in teachers’ daily work, particularly in the development of explicit decisions relating to work and teaching.

Research results from a survey conducted by the Southern African Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) on the conditions of schooling and the quality of primary education has demonstrated that little success has been achieved in improving the quality of education, particularly at the primary level. This survey included several countries, amongst them Zanzibar, Namibia, Lesotho, Botswana, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, and South Africa. The SACMEQ (2004) report pointed out that the academic results at the primary level are very poor. The report states that, at the national level in Namibia, in 1995, only 22.7 % of learners reached the minimum level of mastery (i.e., likely to barely progress to the next grade) in reading literacy and a meager 7.8 % reached the desirable level of mastery (i.e., high likelihood of progressing to the next grade). In comparison, the figures for the year 2000 show a decline in the percentages of learners at the minimum and desirable levels of achievement, with 16.9 % of learners having a minimum level of mastery and only 6.7 % of learners having the desirable level of mastery. These results show a worrisome situation, indicating that the commendable expansion of the provision of access to primary education has not been accompanied by a corresponding improvement in the quality of learning outcomes. In Namibia, this was attributed partly to the lack of a comprehensive Early Childhood Development programme, and pre-primary education interventions are needed for better educational outcomes. Accordingly, the ETSIP (2007) programme identified early childhood development and pre-primary education as playing a central role in the overall development of children and their chances of future success in school.

The classroom as a factor

According to research, the class experiences and teaching have a greater effect on learning results than the general policies and operations of the school (see Wang et al., 1994), highlighting factors like the feeling of affinity for the class, reward structures, goal orientation and workable routines. When the classroom is examined as a workplace, factors like the functionality of the room and furniture, an appropriate interior design for teaching, sufficient lighting, and a peaceful workplace ambience collectively rise to importance.

Students generally respond well when the teacher uses various sensory modalities during teaching. In lower grades, students enjoy the use of a combination of visual and tactile cues in addition to the use of intrinsic motivators. Also significant for learning is how much time students take to perform given tasks and how often they perform tasks in which they can succeed. In addition, attention must be paid to the way homework is inspected and to the feedback students receive from the teacher and each other. These actions affect, for example, the meanings that children assign to tasks and the work they perform, and help to guide children’s attention towards matters essential for success.

From the viewpoint of classroom functionality, the teacher’s skills in managing and guiding the class are vital. This includes efficient daily practices and the use of teaching materials, as well as controlling disturbing factors and problem behaviour within the class. The amount and quality of interaction in learning and teacher-student relations also affect the efficiency of learning. Interaction in learning includes, for example, feedback from the teacher, various questions asked by the teacher and instructions concerning knowledge enrichment, all of which affect the development of the child’s information structures. Furthermore, social interaction outside of teaching situations is particularly important for the development of the child’s self-esteem and feelings of affinity, which are known to affect learning results as well.

The content and quality of teaching can be assessed, for example, by examining the way that the teaching content is presented and considering the practices used to instruct students. For example, in Zambia the Primary Reading Programme (PRP) was introduced to help improve reading and writing skills for children in all Government schools from grade 1 to grade 7. Under this programme, the teaching of initial literacy is conducted using the New Breathrough to Literacy (NBTL) course in grade 1. In this course initial literacy is taught in each of the seven official Zambian languages, each language catering for a specific region of the country. In grade 2, the Step Into English (SITE) course is used. This course enables the transfer of the literacy skills from the Zambian languages to English. From grade 3 to 7, the Read On Course (ROC) consolidates what was taught in grades 1 and 2 in both English and the Zambian languages.

The various syllabi used in the basically aid the teachers in the preparation, organisation and presentation of the daily lessons by providing guidance in terms of subject content and how this content can be effectively presented in line with a particular grade level. The content material is designed based on the overall learning objectives and desired outcomes for the children, as stipulated by the Ministry of Education. This is not to say that the teachers themselves have no say in what and how they plan their daily lessons. It just means that they are expected to impart the pupils with specific knowledge as indicated in the syllabus, yet in conjunction with this the teachers are generally expected to use their own initiative and innovation to ensure that the material is presented in a manner that will ensure that their pupils grasp the relevant concepts and skills. In the process of preparing daily lessons, most teachers need to take a number of factors into consideration, such as the class size, the pupils’ current level of knowledge, availability of teaching and learning resources, available time and the general progress of the class, to mention but a few.

The lack of adequate teaching and learning resources is a problem that is faced by many African countries. The lack of teachers in some schools, especially rural schools, affects the learning and teaching process in more general. The number of students is quite high in most classes, with an average of about 50–60 students per class, depending on the location of the school. For example, in Kenya and Zambia, primary education is free of charge, which enables even children from poor homes to receive an education. Due to a lack of resources, this initiative has led to an average of 150 students per class in some public schools in Kenya, in both urban and rural areas. School resources are therefore stretched. The more students there are in a classroom, the more resources are required. Unfortunately, adequate teaching and learning resources, such as sufficient furniture, books and classrooms, are not always available, hindering the learning and teaching process. It must be mentioned, however, that the respective governments are trying by all means to ensure that everything that is needed for children to learn is available.

World Bank studies (Marope, 2005) have pointed out serious lapses with regard to literacy levels and language learning in African countries. The study (Marope, 2005) found that the shortage of textbooks and instructional materials persists especially in primary schools. Other than textbook shortage, schools are characterised by inadequate instructional materials such as student workbooks, teaching aids and enrichment materials. At the end of a school year, learners progressing to the next grade often do not pass their materials from the previous grade on to the new learners even though print materials for reading are rare both in schools and homes. The study also found practicing teachers to have poor reading and grammar skills, weak elicitation techniques, limited vocabulary, as well as limited facility to adequately explain concepts. Marope (2005) argued that teachers’ poor English proficiency in African schools adversely affects instruction, not only in English as a subject, but also in all other subjects that are taught in English. This is crucial in school systems such as that of Namibia, for example, which uses the English language as a medium of instruction from grade 4 onward. Similar to Marope (2005), Sinalumbu (2002) concluded that factors contributing to poor literacy attainment in Namibia include overcrowded classrooms, poor teaching, primary language interference, and lack of parental support in learning to read and write. Also concerning Namibia, as an example of African schools using the English language for classroom instruction, Kuutondokwa (2003) documented the lack of reading materials in schools and homes, illiterate parents, lack of assistance from teachers, improper motivation to read, lack of printed materials in local languages, automatic promotion, poor teaching and poor teacher training programmes, as aspects that warrant attention if the nation is to improve its literacy development and children’s rate of school attendance.

The culture and language of instruction as factors

The issue of several languages being spoken in most of the African counties is essential in respect to school instruction. For example, Namibia has 13 languages of instruction for grades 1 – 3. The writing of some of these languages is still evolving. Standardisation of orthographies and the production of learning materials are recent phenomena that teachers are still getting accustomed to. Because of teachers’ language limitations, reading and writing lessons tend to be imparted with a rather mechanical-sounding verbalisation of words without grasping meaning or context, and likewise copied by the children in the classroom. Given their own challenges, teachers have little facility to identify, assess and intervene in pupils’ learning problems in order to help them with their reading and writing difficulties.

Transitional bilingual education is a common type of educational system, such as in Namibia. Initial literacy learning in the mother tongue is crucial to establishing a positive self-image, an affirmation of one’s own culture, and a greater understanding of the world us. For instance, in Namibia, language skills and literacy tend to first be developed in the mother tongue, until a learner is thought to be proficient enough in his/her mother tongue to cope in mainstream education. It is recognised that children learn best when they are taught in their own mother tongue. After being confident and well-equipped in their mother tongue, mastery of another language under optimal circumstances is considered not to be a problem – a view that is held by several theorists as we shall see. The primary concern in using the mother tongue in instruction is the ability to ensure that all learners acquire the skills which will lay a strong foundation for literacy, communication, and concept formation in numeracy, all of which are crucial in regard to the learner’s future education (see Namibian Ministry of Education, Lower Primary Phase Syllabus, First Language, 2005). The aim of the transition, as argued by Baker (2003), is to gradually increase the use of English in the classroom while proportionately decreasing the use of the mother tongue language in the classroom. This policy of transitional bilingual education promotes the early exit from mother tongue instruction to English instruction. For this to succeed, the teachers at these levels need to be bilingual in order to promote the transition from home language to school language, which is not always the case.

The home as a factor

The significance of the home for efficient learning has always evoked discussion. The family’s primary duty is to offer the child care and nurturing, but the family is also important for the child’s studies. At their best, the family’s actions and attitudes support learning. An appreciative and supportive attitude toward studying is seen, for example, when parents show interest in their child’s school and participate in school events. They supervise their children’s homework and they have expectations concerning school success. When a child is confronted by problems in learning, the parents’ most important task is to offer appreciation and security. In these situations, cooperation with various parties, and sometimes even fighting for the child’s rights, is called for from the parents.

In African countries, many parents also have problems in their own education which might influence the child’s motivation. Research by Gachathi (1976) indicates that there is a high positive correlation between the level of parents’ education and their children’s achievement motivation. Furthermore, Mbenzi (1997) argued that socioeconomic background plays a role in learning to read. He argued that many parents were illiterate and could not render assistance in literacy learning. Poverty has also been pointed out as a stumbling block as disadvantaged parents cannot afford to buy books to share with their children, while affluent parents can purchase the necessary materials for learning. Also, in 2004, in research by the SACMEQ, it was reported that the reading competence of learners from low socioeconomic groups was much lower than that of learners from high socioeconomic groups. In 1995, only 11.1 % of learners at a low socioeconomic level reached the minimum level of mastery, while 34.1 % of learners at the high socioeconomic level reached the minimum level of mastery. The desirable level of mastery for the same year was 1.2 % and 14.2 %, respectively. In the year 2000, only 5.9 % of learners at a low socioeconomic level reached the minimum level of mastery, while 31.9 % of learners at the high socioeconomic level reached the minimum level of mastery. The desirable level of mastery for the same year was 0.8 % and 14.9 %, respectively.

Many African parents, like many other parents around the world, value education for their children. There are different forms of education, but the most prestigious is the formal type of education obtained through academic studies. Not only is it viewed as a source of status for both the family and the individual, but it is also viewed as a means to a better life by the whole community. That is why many African parents make huge material sacrifices to ensure that their children have everything they need to go to school and succeed, saving money for school fees, uniforms, stationary, books, and transport to school among other needs. While there are some parents who may be able to assist their children with school related activities, such as helping with homework or reading with their children, there also exists a large number of parents who are unable to provide this kind of assistance because of their own lack of education. Their lack of education may mean that they are unable to assist with academically oriented activities at home, but it does not take away the hope, desire and motivation to see their children succeed and achieve more than they have as parents. This motivation, enthusiasm, encouragement, faith and hope (all necessary for success) for a brighter future is what they impart to their children.

What does efficient learning require from the student?

The foundation of learning is the child’s inherent curiosity and desire to learn and control himself/ herself and his/her environment. The child is naturally motivated to learn new things and to meet new challenges. Motivation is maintained, for instance, by experiences of success and the joy of mastering new skills. Sometimes this joy and enthusiasm receive such strong blows that the child’s faith in his/her own abilities is weakened and the child subsequently loses the courage to tackle new tasks. Recurring failure may weaken the child’s self-concept as a learner and member of the classroom community to the extent that learning loses its appeal and the child does not learn according to his/her potential. In addition, the child’s courage to face challenges and his/her ability to take initiative in problem-solving situations, as well as to engage in teaching and classroom activities, is diminished. In such a situation, the child needs substantial and prolonged support from his/her peers, significant adults and from the community in general in order to regain faith in his/her ability to learn new knowledge and skills.

Along with age and experiences at school, the child learns to improve his/her working skills. A positive self-concept and metacognitive knowledge and skills that are acquired alongside the skills learned at school and through experience, help the child to develop study practices that are most suitable for him- or herself. These skills are also highly significant for the child’s ability to benefit from teaching and the use of educational materials in his/her coming school years. Research on study-efficacy has revealed the particular importance of metacognitive knowledge and skills, which are essential since they have an impact on the child’s ability to be successful in learning situations and school activities, as well as influencing the ability to apply and generalise what they have learned and to monitor and evaluate their work as an individual and in the group. Children themselves are seldom aware of the strategies they use, which is why adults should pay attention to their child’s lack of strategies for studying or their ineffectiveness. If the child has poor work and study skills, then he/she cannot set goals for him- or herself, nor for studying – this makes it difficult for a child to begin work and to carry it through to completion. The child’s attention may also be diverted by irrelevant issues, or he/she may get stuck on a counterproductive way of carrying out a task – such a child is often dependent on the presence of an adult or on repeated guidance.

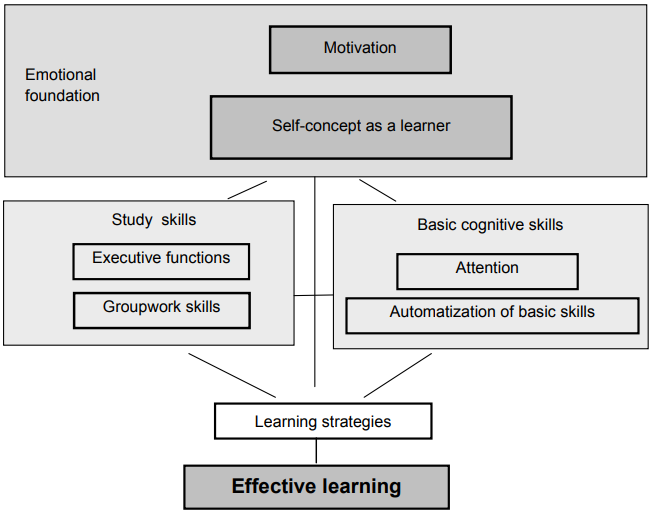

Figure 1. The cognitive and emotional prerequisites for effective learning (modified from Meltzer, 1996).

Strong motivation, a positive self-image, and proper study practices and strategies are prerequisites for effective learning. All of the factors which contribute to ineffective learning, as described, are presented in Figure 1. Sometimes these sustain substantial deficits that can hinder learning significantly. Furthermore, properly directed motivation, a positive self-image and effective learning strategies are not always enough to ensure fluent and easy learning of skills. The ability of some children to learn new skills is notably weaker than that of their peers. They need frequent repetition and more practice, or perhaps different teaching methods, in order to learn new skills and to use them as tools for further learning. A child may also have insufficient skills in focusing and sustaining his/her attention. In such a case, a developmental problem that hinders the assimilation of basic skills is responsible for the difficulties in learning. The term “learning disabilities” is usually used with these children.

To understand difficulties in a child’s learning, we must assess several factors that affect learning. By assessing the tasks and situations that cause difficulties, we can clarify what is necessary for the child to succeed in those tasks and situations. Assessing the development of the child’s cognitive skills and emotional development helps to understand his/her strengths and weaknesses. Assessing the learning environment, for its part, tells us how the combination of the child’s characteristics and the demands of the task and situation affect learning, as well as revealing what kind of support and challenges the child is experiencing. The goal of learning disability assessment is to produce knowledge of these different factors affecting children’s learning and to understand how these factors are interrelated.

In learning disability assessment, information is synthesised with the child’s developmental history, the phenotypes of the problems and the environmental factors. Light is also shed on their interaction. Successful learning disability assessment and support planning require the close cooperation of the adults involved in the child’s education. Among other factors, it helps those working with the child to understand the following obstacles in learning:

- Poor motivation or negative self-image as a learner: What has caused their negative development?

- Difficulties in learning basic skills: What kinds of developmental problems are behind these difficulties?

- Lack of learning strategies: What has hindered the learning of effective strategies?

- How do these difficulties interact?

In order to provide answers to these questions we must evaluate a whole series of developmental factors and educational activities, all of which involve the learner, the parent and the teacher.

What are learning difficulties or disabilities?

A learning disability is seen on a functional and behavioural level, in the slow or abnormal learning of new skills. Among school-aged children, difficulties may be seen as deficient skills in

• reading,

• spelling and writing,

• reading comprehension,

• mathematics,

• problem-solving, and

• attention.

According to the diagnostic definition, learning disabilities are thought to be developmental disorders or differences (most often based on genetic factors affecting the development of the nervous system already before birth) that are not due to mental disabilities, neurological disorders or illnesses. A significant criterion, according to the definition, is that deficits in cognitive functions prevent achieving the learning objectives of the age group in spite of sufficient schooling and teaching. The student should receive sufficient teaching, which means special education for the slower learner. But we have to remember that learning difficulties also appear in connection with diagnosed neurological injuries or illnesses (such as epilepsy or traumatic brain injuries), and their scope depends on the location and extent of the injury or the nature of the illness. Neurological injuries and illnesses can also extensively delay the general development of the child. It is thought that in developed countries, with well-developed health care systems and services, the aetiology of learning difficulties is most often genetic. However, the situation may be much different in less developed countries, such as the African nations, where considerable problems in health care systems increase the neurological risks affecting children. Additionally, sufficient teaching is not guaranteed in African countries, chiefly due to inadequate resources to cater for both the gifted and challenged children.

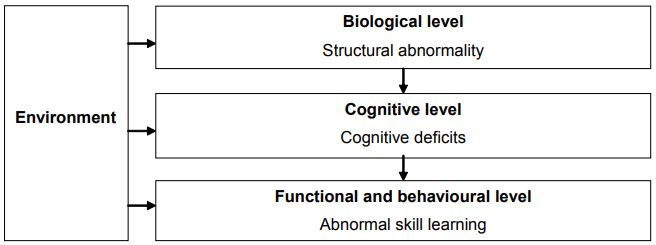

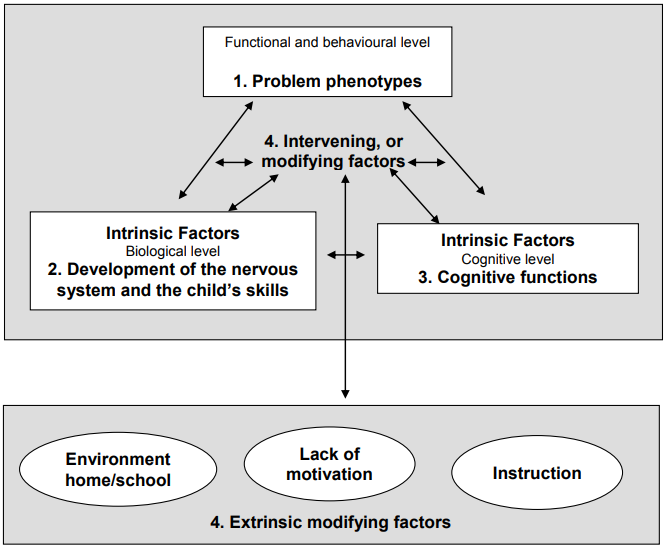

In general, deficits in cognitive functions are believed to be behind learning disabilities. The cognitive characteristics typical for each learning disability are examined in detail in later chapters. An abnormal or atypical organisation of cerebral functions – the causes of which are not yet fully understood – is thought to be behind cognitive deficits. It is commonly believed that an abnormal development of the nervous system results from the overlapping of many different factors of which biological factors, such as heredity, form a significant portion (see Figure 2). Pre-, peri-, and postnatal events may also be significant. This complex relationship between hereditary and environmental factors can be represented as follows:

Development = f(H x E x T), where

f stands for the “function of”

H refers to heredity, i.e., our inherited traits

E stands for the effects of environmental agents which include familial experiences as well

as school and health factors etc.

T is for the passage of time

The above relationship indicates that the three variables (H, E and T) play an interactive role

in influencing an individual’s quality of development.

Figure 2. A three-level explanatory model of learning disabilities (Frith, 2001).

A rough distinction can be made between developmental problems detected before schoolage which become manifest as learning disabilities during school-age, and learning disabilities that emerge at the onset of school or later. Developmental problems manifest themselves as problems in the development of attention, language, visual-spatial perception, motor or social skills, or as combinations of these problems. In many cases, such problems manifest themselves before the child reaches school-age, meaning a diagnosis can be made even before the child attends school.

Learning disabilities that arise during the school years are generally difficulties in learning the basic skills taught at school. Most common are learning disabilities in reading, spelling/writing, and mathematics. The aforementioned developmental problems are often behind these difficulties as well, but often the developmental problems (e.g., problems in language development or mild motor difficulties) have been moderate or undetected prior to the child reaching school-age, or they have been diagnosed as insignificant, resulting in the child not receiving any special support. In Finland, it is a common procedure in the examination of five-year-olds at the child health clinic to make a more detailed assessment of the child’s development than on earlier visits. This offers an opportunity to detect any possible delays or deficiencies in development and to commence with relevant support for the child before school begins. Also in Kenya and other African countries, possibilities for early identification do exist due to the rapid enhancement of services for the children with special needs there; however, a lot of children have not yet received these very essential services.

What other factors may impair learning?

Learning disabilities are not the only cause for difficulties in learning. It is often hard to distinguish a learning disability from a learning difficulty caused by something else, or to draw distinct boundaries for when a child has a learning disability and what the cognitive deficit is that predisposes them to the disability. A defining issue in so-called specific learning disabilities has traditionally been the difference between the child’s general intellectual capabilities and his/her specific learning results. According to this thinking, developmental difficulties and learning disabilities appear as a slower development in some specific skill area.

However, the notion that learning disabilities can also be detected in those children and adolescents who have wide-ranging cognitive deficits is gaining ground. According to this school of thought, for instance, the cause behind reading disabilities is a difficulty in processing phonological information, which impairs learning to read regardless of the person’s general performance level. Additionally, a familiar phenomenon in practical work is the so-called Matthew Effect, in which difficulties in one function gradually expand their effect to other areas as well. For example, the consequences of deficient reading skills can be seen in poor performance even in tasks that do not demand reading. Infrequent reading results in, for example, meagre accumulation of general knowledge and vocabulary, low self-esteem and motivation, and poor general performance in both school and test situations. Thus, the modern understanding of the relationship between learning disabilities and general aptitude is not as unambiguous as it is in some of the more traditional definitions of learning disabilities.

Biological risks (such as chromosomal and genetic anomalies) do not directly define the phenotype of learning disabilities. Various factors pertaining to the child’s environment, social relations, interaction and motivation determine the forming of reciprocal relationships between nervous system development, abilities, skills, performance and behaviour. We can also assume that there are children without serious risk factors affecting their cognitive skills or nervous system development, but whose disposition towards learning disabilities is realised in unfavourable circumstances. Factors in the child’s environment can amplify or highlight problems with learning. Respectively, an environment that supports the child’s development may deter learning disabilities or prevent their deepening or expansion. For example, it has been observed that the impact of early developmental risk factors on a child’s development is also connected with his/her growing environment and the support that the child and his/her family receive, rather than only with the original biological risk. While studying a child’s learning skills and knowledge, one should assess whether there are factors in the child’s life that obstruct or hinder his/her learning and school attendance. Such factors may be, for example:

- teaching and school-related problems (e.g., number of pupils in the class, education of

- the teacher, teaching materials and books),

- insufficient nutrition or sleep,

- health problems,

- problems in the child’s emotional development and security,

- the effect of a family member’s emotional problems (e.g., anxiety or depression) on the child,

- violence in the family,

- social/economical problems of the family, and

- ambiguous daily routines at home or school, insufficient support.

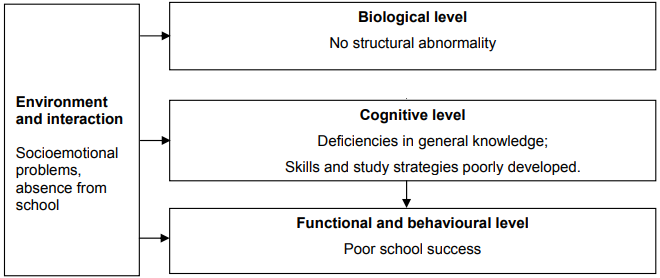

Problems in learning due to the aforementioned factors, may manifest themselves in daily situations of difficulties with schoolwork, similarly as with learning disabilities (see Figure 3). A picture of the child’s daily life and family’s situation can be formed by carefully gathering developmental information and evaluating the school and family situation. Sometimes it can be noted that risks in the child’s environment coincide with cognitive-based learning disabilities. In such a case, it is important to form as comprehensive a picture as possible of the factors affecting the child’s learning, for the sake of successful support planning. In Africa, schools are considered to be the society’s property, which is why school boards have a very strong representation of parents. Teachers are held accountable for pupils’ performance, sometimes to unrealistic levels – especially regarding the children with learning difficulties (Ondiek, 1986).

The assessment of learning disabilities and the discernment of these from learning difficulties caused by external factors is even more challenging in African countries than in Finland. This is readily seen in the results of Nepando (2003), who concluded that poor preschool services, poor teacher training and preparation, poor learner motivation, reading anxiety resulting from labelling, grouping, humiliations and unfair treatment of poor readers and writers resulting in emotional block, lack of support services to help teachers and parents with children who find it difficult to master literacy skills, overcrowded classrooms with no room for individual attention, and insufficient teaching and learning materials, are all affecting literacy development amongst African children.

Figure 3. Problems in school attendance due to socioemotional factors (according to Frith, 2001; cf.,

Figure 2).

Knowledge of the child’s general situation in life and the typical characteristics of learning disabilities can be used to support evaluation. Firstly, learning disabilities do not usually appear suddenly or as a regression or loss of skills. Usually, slower development of specific skills has been apparent during the child’s growth, or the child has achieved certain developmental steps a little bit later than is typical for his/her age group. The basic skills taught at school can also be seen as developmental steps. For example, learning to read is normally a developmental and educational extension of advanced language skills. Assessment may be helped by the fact that the child’s parent or near relative has often had similar problems in their learning.

Another question is whether or not it is always necessary or possible to discern the cognitive and emotional factors behind a learning problem. Difficulties in learning are often accompanied by several other simultaneous difficulties. For example, emotional problems may be either independent or consequences of the child’s learning disabilities. Additionally, emotional problems can sometimes produce problems in learning. It is not always possible to uncover the relationship between the difficulties, but even in such a case, it is important to plan sufficient support, which at its best provides diagnostic information, and to ensure follow-up.

References

Atkinson, J. W. & Raynor, J. O. (1974). Motivation and Achievement. Washington: John Wiley &

Sons.

Baker, C. (2003). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 3rd Edition. Clevedon:

Multilingual Matters.

Christenson, S.L. & Ysseldyde, J.E. (1989). Assembling student performance: an important

change is needed. Journal of School Psychology, 27, 409-425.

Frith, U. (2001). What framework should we use for understanding developmental disorders?

Developmental Neuropsychology, 20, 555–563.

Gachathi, P. (1976). National Committee on Educational Objectives and Policies. Nairobi: Government printer.

Horowitz, F.D. (1992). The risk-environment interaction and developmental outcome: A theoretical perspective. In C.W. & J.G. Auerbach (Eds.), Longitudinal Studies of Children at Psychological Risk: Cross-nationalperspective. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Kuutondokwa, S. (2003). Reading Difficulties in Lower Primary Rural Areas Schools. Fieldwork

Report: University of Namibia, Windhoek.

Meltzer, L. (1996). Strategic learning in students with learning disabilities: The role of self-awareness and self-perception. Advances in Learning and Behavioral Development, 10B, 181–199.

Marope, M. T. (2005). Namibia Human Capital and knowledge Development for Economic Growth

with Equity. World Express, African Region.

Mbenzi, P. A. (1997). Analysis of reading Error patterns of Grade 5 learners at Namutoni Senior

Primary School and how to overcome them. Fieldwork Report: University of Namibia, Windhoek.

Ministry of Education. (2005). Lower Primary Phase Syllabus, English First Language.

Ministry of Education. (2009). Education and Training Sector Improvement Plan (ETSIP). [Online]. Available: http://www.mec.gov.na/ministryOf Education/etsip.htm [2009, June 27].

Nepando, J. T. (2003). Reading Problems Experienced by Selected Learners in Selected Schools in

Namibia. Fieldwork Report: University of Namibia, Windhoek.

Ondiek, P. E. (1986). Curriculum Development: Alternatives in Educational Theory and Practice.

Nairobi: Lake Publishers and Enterprices.

Republic of Namibia, (2003). 2001 Population and Housing Census National Report, Basic Analysis with Highlights. Windhoek, National Planning Commission.

Reynolds, D. (1997). School effectiveness retrospect and prospect. Scottish educational Review,

29, 87–113.

Rourke, P. & Del Dotto, J. (1994). Learning Disabilities. A Neuropsychological Perspective.

Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

SACMEQ. (2004). A study of the conditions of Schooling and the Quality of Primary Education in

Namibia. By D. K. Makuwa, National Research Coordinator.

Sinalumbu, F. S. (2002). Examining Reading Difficulties of Grade 7 learners within a School in

Oshakati. Fieldwork Report: University of Namibia, Windhoek.

Wang, M.C., Haertel, G. D. & Walgerg, H.J. (1994). What helps student learn? Educational

Leadership, January, 74–79.

Mika Paananen, Pamela February, Kalima Kalima,

Andrew Möwes and David Kariuki

2. Learning Disability Assessment

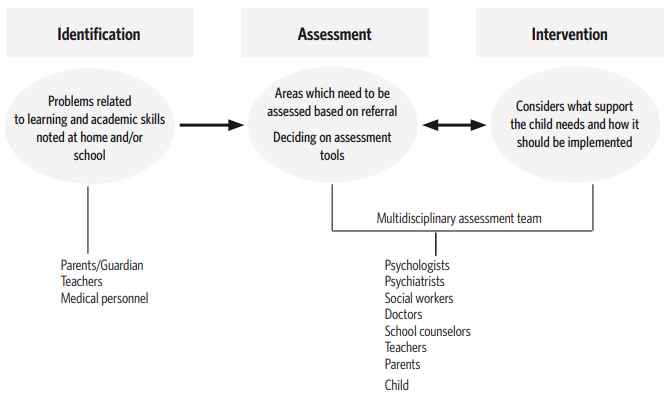

Learning disability assessment begins at school

In Finland, assessment of the causes of learning disabilities usually begins when the parents (or other guardians) or the teachers are worried about the child’s learning progress (see Figure 4). This is usually followed by the special education teacher’s assessment. In cooperation with the class teacher, the special education teacher evaluates, for example, whether the child has difficulties in reading, spelling, or mathematics. In Finland, the special education teacher can also quite precisely determine how extensive the difficulty is and what kind of support the child needs. When the teacher’s evaluation seems insufficient and additional help is desired in planning support, the child or adolescent can be referred to the school psychologist, family counselling centre, or health centre for further assessment. This further assessment is necessary when

• in spite of diligent work and special education services provided, the child does not learn according to expectations;

• the school’s own evaluations and assessments do not seem adequate (for example, there is reason to suspect an extensive problem that the special education teacher’s methods failed to assess);

• the school requests assistance in planning appropriate educational support;

• the school requests assistance for smoothing out disagreements between the school and the home;

• the family, teachers, or the child are worried about changes in the child’s learning;

• clear regression has occurred in the child’s skills;

• an appraisal is required of the need for support and intervention services from a party outside of the school.

Figure 4. Multidisciplinary approach to assessment and intervention of learning disabilities

In Zambia, for example, the process of assessing learning disabilities, at its highest level uses a similar format to that in Finland. Most of the problems are initially spotted by parents when their child is not making adequate progress in school. In some instances, the teacher may notice that the child is not making adequate academic progress and subsequently asks the parents to consider taking the child for assessment. The teacher may also contact the assessment personnel directly and request for an assessment to be conducted, which would of course only take place with the consultation and permission of the child’s parents. Currently, Zambia’s Ministry of Education has a policy to ensure that children are assessed in order to determine their specific needs before they can be placed in a special school. The Ministry even makes some of the referrals to the assessment centre where a detailed assessment can be made. There are other instances when doctors at the paediatric and mental health hospitals send children to the assessment centre to determine the level of functioning of the children. At the paediatric clinic, the assessment often aims at establishing the learning needs of the child. The referrals to the mental health hospital are often children with special needs who may have been abused or defiled, in which case the courts require an assessment in order to establish the child’s functional level.

Needless to say, there is quite a large variation between the African countries with respect to the available resources and the way educational policies are applied in terms of identification, assessment and intervention, but what is common to all these countries is the need to do more for children who have a learning disability. In Zambia, most of the children with learning disabilities are “diagnosed” without necessarily undergoing a proper assessment. To improve this situation, assessments should be made mandatory by law for the benefit of all children before they are placed in special schools. However, in Zambia, the services of psychologists are not available for many people since, to a large extent, psychologists are found only in the capital city of Lusaka. It is therefore imperative to decentralise the services of psychologists in order to also make them available at provincial and district levels. Currently, the idea of having a multidisciplinary team including a psychologist, a school doctor and a trained special education teacher to deal with children’s early assessment is still a dream in many African countries. Furthermore, in African countries, most assessment instruments that are currently in use for the diagnosis of learning disabilities are standardised using Western norms. This raises ethical issues as a lack of sensitivity to cultural differences can result in misdiagnosis or mislabelling. More effort should be made to standardise assessment tools to include the local norms.

Assessments by classroom teachers and special education teachers

Early childhood has been recognised as a crucial stage in human development, not just in African countries, since it forms each individual’s foundation for subsequent development and learning, further underlining the need for more educational resources. Early identification of special needs in young children is a process or service that has gained popularity in recent years. This is because it is hoped that it will be easier to prevent serious problems and reduce the impact of a disability at an early stage of development. Identifying problems in young children is not always an easy task, but it is a worthwhile to undertake, especially for the purpose of preventing more serious difficulties from occurring later on.

The identification of learning related difficulties begins already when a teacher has a feeling or intuition that something may be wrong with a child, or that a child does not perform according to his/her best ability. It is then the teacher’s duty to investigate that notion in order to confirm or refute it. In such a case, initial identification of learning related difficulties is primarily based on the intuition of the teacher. Intuition, however, is always based on something – it is not simply a matter of coincidence, but arises from a knowledge and insight concerning the child’s educational situation. Factors heightening a teacher’s intuition include dedication and empathy, which motivate the teacher’s interest in each student within the class. Teachers should never regard any worrying behaviour or comments by students as coincidental, but should always try to relate them to possible problems that the child might be experiencing at school or at home, as these problems may affect the child’s development towards adulthood. However, teachers should take care not to misunderstand a student either, as this could cause them to label the child incorrectly as a person that he/she neither is nor wants to be. Teachers should therefore seek to find concrete evidence to support their intuition by systematically observing the child in different situations.

Sometimes parents are the ones who may suspect that their child has certain problems or special needs, leading them to mention these to the teacher for further investigation. Parents who are interested in their children are seldom wrong in their intuition about problems that their children might be experiencing. However, the combined intuition of both teacher and parents does not constitute sufficient grounds for a confirmation of the child’s special educational needs. There are three basic skills that teachers should master before they can successfully identify any problem a child has, namely observation, screening, listening, and questioning.

Observation: Observation can be explained as a “visual inquiry conducted through systematic observation.” Teachers should begin their observation without any preconceived ideas about the children in their class. By minutely observing children’s behaviour in the classroom, on the sports field and during other extramural activities, one can conclude whether a child manifests any unusual behaviour. In the classroom, the teacher should note whether a student’s current behaviour differs from his/her normal behaviour. This also applies to conversational situations and working sessions. The teacher may ask him/herself, “How does the child act towards other learners?” or, “Does the child behave differently in different situations?” A child’s nonverbal communication with the teacher and other students, as reflected in body posture, facial expressions and gestures, should also be carefully observed to determine the nature of the child’s emotions within the learning environment.

Additionally, teachers should be aware of serious or even mild ailments a child in the classroom may suffer, such as relating to asthma and migraine, impaired vision or hearing, epilepsy or motor coordination problems, as well as malnourishment or undernourishment. The sooner these conditions are identified and the affected children receive treatment, the less impact they will have on the child’s achievement in school.

Screening: Screening is a technique for acquiring information about a great number of people in as quick a time as possible. The results of tests and examination papers can be used as screening methods to identify those children whose results are poorer than they were expected to be. It may be that a child is diligent in class (e.g., first to answer questions) but does not perform well on examinations. Such a child may be singled out for further diagnosis.

The psychological assessment

The psychological assessment is more extensive than the teacher’s pedagogical assessment, and it seeks to understand the child’s learning difficulties in relation to the his/her entire cognitive performance profile and earlier development. This makes it possible to detect and exclude other factors that affect learning (e.g., more comprehensive developmental problems, environmental factors). Learning disability assessment may be an independent process or part of a broader analysis by the psychologist of the child’s life situation, including evaluating the development of the child’s emotional life and personality. Additionally, a well-trained special education teacher can also perform a comprehensive learning assessment. The extent of the assessment to be performed is determined by how problematic the child’s situation is felt to be, how multifaceted the problems seem, and by the results of earlier assessments, which usually help to direct and focus the current assessment questions.

In addition to the overall extent of the assessment required, its nature is determined by the child’s school history at the time in which the assessment is to take place. If the child is assessed when there is yet but a mere suspicion that he/she is not learning at the same pace as his/her peers, the results are likely to show that the difficulties have not necessarily affected the child’s life very broadly thus far. In such a case, the learning disability’s effect on the child’s self-esteem and school motivation may only be minor. But if the assessment is to take place when the child’s difficulties are already evident to such a degree that there is great concern over e.g., his/her progressing to the next grade, then the type of assessment needed will be of a different nature. In such a case, the parents may already know a lot about their child’s difficulties and many forms of support may have already been tried at home and at school to support the child. The child may also be quite aware of the nature of his/her own learning difficulties and these may have already had considerable ramifications in the child’s life. Whatever the starting situation may be, the psychologist must, naturally, use his/her own judgement to consider the direction and extent of the assessment.

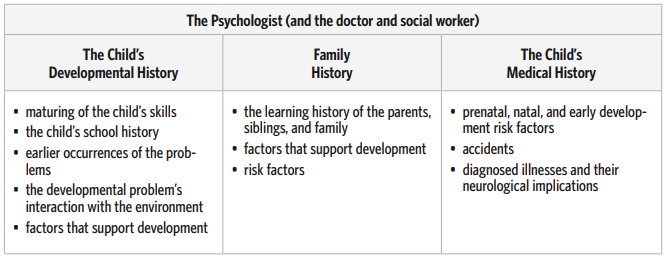

The learning disability assessment conducted by a psychologist can be divided into four different procedures, each of which requires gathering information from several parties:

1) assessment of the phenotype,

2) developmental history,

3) assessment of cognitive functions, and

4) modifying or intervening factors.

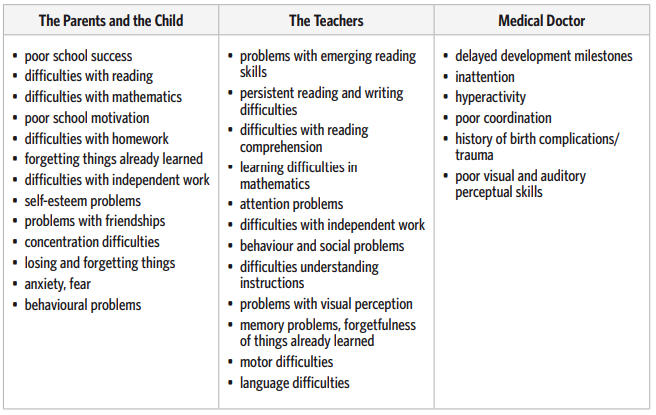

Phenotype: Learning disability assessment is usually begun with the procedure of examining the child’s functions and behaviour, or in other words, defining the phenotype problem (see Figure 5 and Table 2). A specific problem could be, for example, dyslexia, difficulties in reading comprehension, or attention problems. The description of the phenotype helps in choosing the right assessment method and facilitates time management. It is also important for choosing the most effective partnerships for cooperation, and it helps to target the assessment as well as the planning of the intervention.

Developmental history: The second standard assessment procedure is to examine the child’s development and its special characteristics and possible risk factors. Knowledge of the child’s developmental history offers more specific information about the history and possible causes of the difficulties or disability. Developmental history is often an important source of information, for example, in questions of differential diagnosis.

Cognitive functions: The third procedure is the assessment of cognitive functions and a more detailed evaluation of the problems detected in the phenotype. This offers detailed information on the nature and causes of the difficulties or disability. Cognitive functions and the assessment of academic skills are discussed in detail later in this book.

Modifying factors: In the fourth procedure, so-called modifying or intervening factors must be examined. These are the child’s environment and interaction with it, and the child’s own experiences. They modify how the problems manifest themselves in the child’s life, as well as determining the appropriate support. Assessing environmental and interactional factors reveals whether the support for the child’s skill level is sufficient or if more extensive support is necessary in the child’s life. The child’s own experiences ultimately determine how he/she reacts in different situations and how problems are interpreted depending on the child’s behaviour. Scientific research has revealed and classified different categories of learning disabilities and in most cases a child’s problem can be matched with some existing category or subcategory. However, the child’s temperament, personality and environment give the problems an individualised expression. Taking this into consideration whilst determining and making an assessment of the child is vital for understanding the whole problem as well as, in particular, for planning support.

Figure 5.The components of assessing learning difficulties (modified from Taylor, Fletcher & Satz, 1984)

Testing hypotheses in learning disability assessments

The goal of learning disability assessment is to provide information regarding the nature of the child’s learning difficulties, its causes, and above all, what kind of support the child needs. Following the model described above, assessment can be understood as a multilevel process. Each assessment procedure is conducted using different methods, providing different information. Together, the different sources of information create a general overview of the child’s difficulties. The assessment process has often been likened to scientific research, as justifiable hypotheses are made about the causes of the detected difficulty. These hypotheses are then tested with the information received on the different levels. The first hypotheses are made from the information in the referral and are expanded upon in the interview. The interview may already uncover new information that disproves one of the first hypotheses. Thus new hypotheses are formed, which are then tested in the assessment. Diagnostic assessment is a process in which reaching conclusions requires information from different sources. The nature and significance of each data collection phase is described in detail as follows.

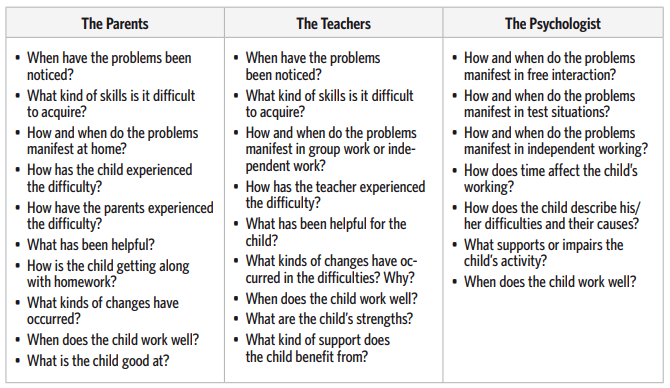

Description of the phenotype problem. Familiarity with the phenotype of the child’s difficulties prior to commencing the assessment is important as it guides the assessment process. The phenotype description facilitates the choice of methods and time management. It also helps in choosing partnerships for cooperation and to add focus to the assessment and later support. Preliminary information about why the child has been sent for assessment and what problems have already been detected needs to be known before the psychological assessment can go ahead. At the onset of the assessment – preferably before the pedagogical or psychological assessment stages – it is good for those conducting the assessment to meet the parents and, if possible, the teachers as well. Parents can talk about how the problems are recognisable in daily life. It is essential to find out what kinds of conceptions and beliefs the parents have concerning the nature and causes of the observed problems and the child’s developmental history. Parents can also share information about the child’s hobbies, interests, and relationships with friends. At the same time, it is essential to find out the parents’ expectations in regard to their child’s learning, information about family interaction, and the amount of support the child is currently receiving (see Tables 2 and 3).

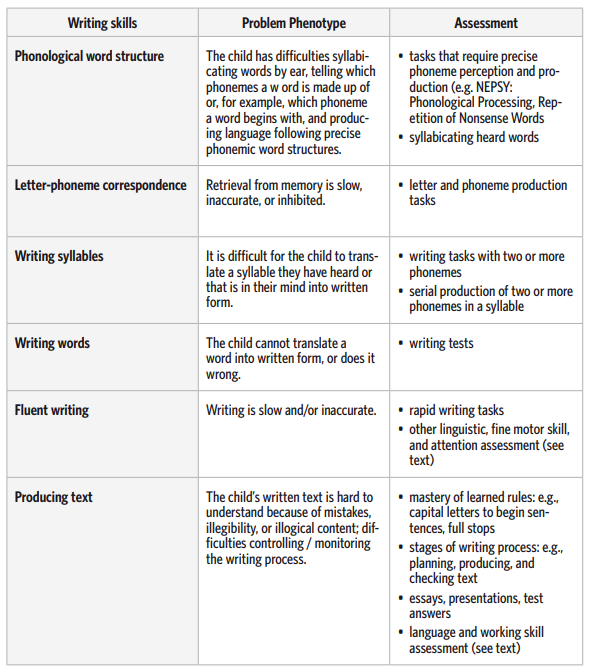

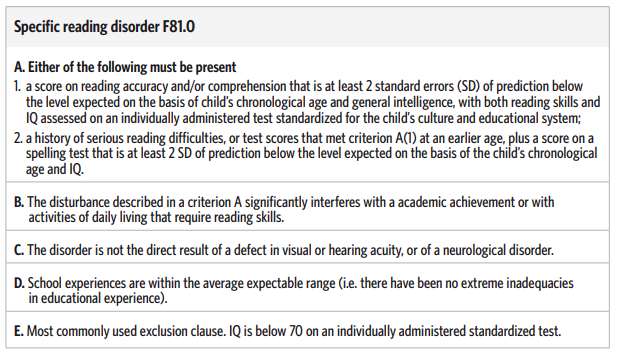

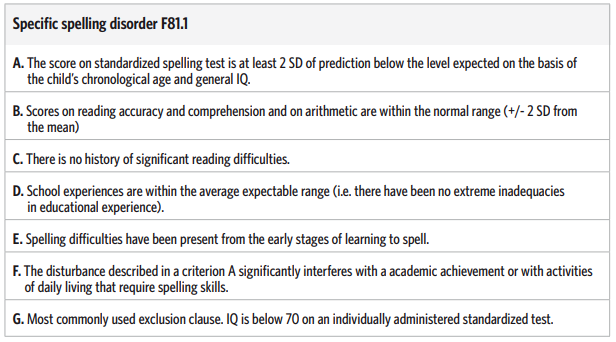

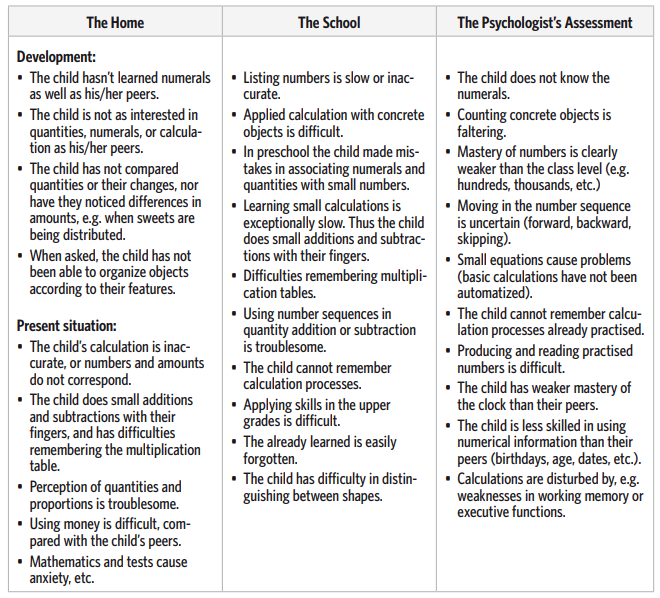

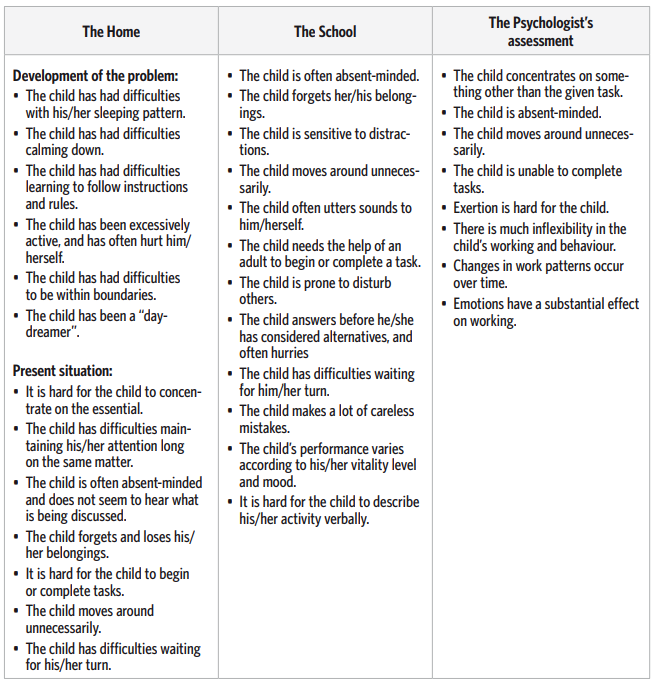

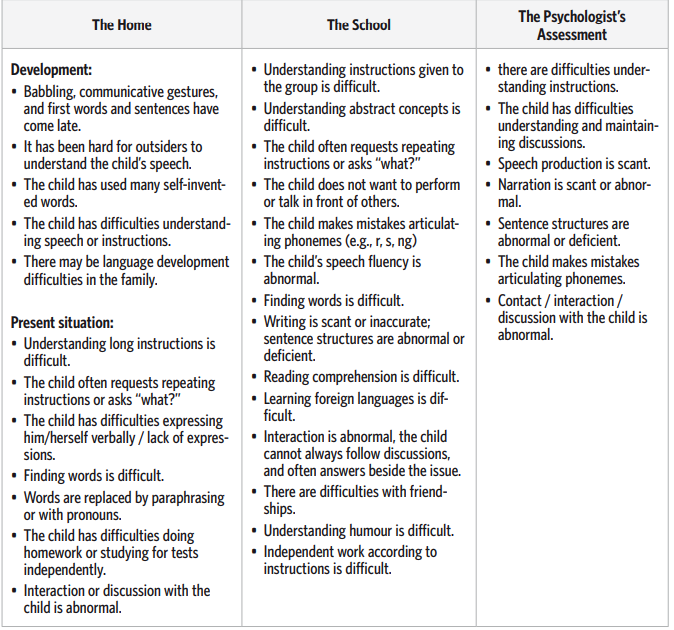

Table 2. Identification of learning disability phenotypes which cause parents, the child, teachers or the family doctor to be concerned

The school teacher’s as well as the special education teacher’s observations of the child are important for the psychologist to determine the phenotype. Teachers have seen the difficulties manifested in class and can share their expectations of the child’s learning potential. They also know about the child’s earlier learning experiences, strengths and weaknesses, working strategies and skill level. They are also aware of the forms of support having been provided. Mapping out child-teacher and parent-teacher interaction, the teacher’s attitude towards the child and the child’s difficulties, and the support available at the school all help in forming an understanding of the child’s classroom life and what type of support is necessary and possible. In Africa, the teacher’s role is mainly to provide instruction, then to evaluate the students in order to find out their level of achievement in relation to the curricular objectives. Evaluation is usually a combination of formative (continuous) and summative (end of term) processes. Feedback from these assessments is meant for use in making rational decisions when developing improvements. Many teachers are successfully able to modify the learning environment opportunities in order to assist the learners with difficulties. It is common for schools to reward students who do well in class, but there is a change, for example in Kenya, towards extrinsic motivators.

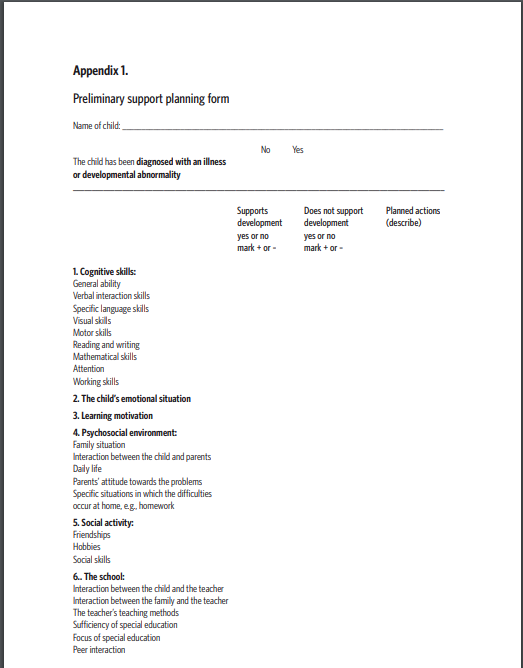

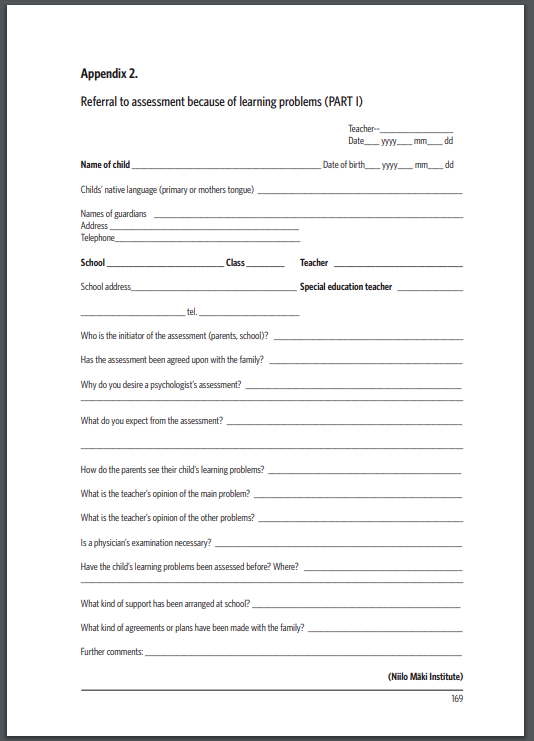

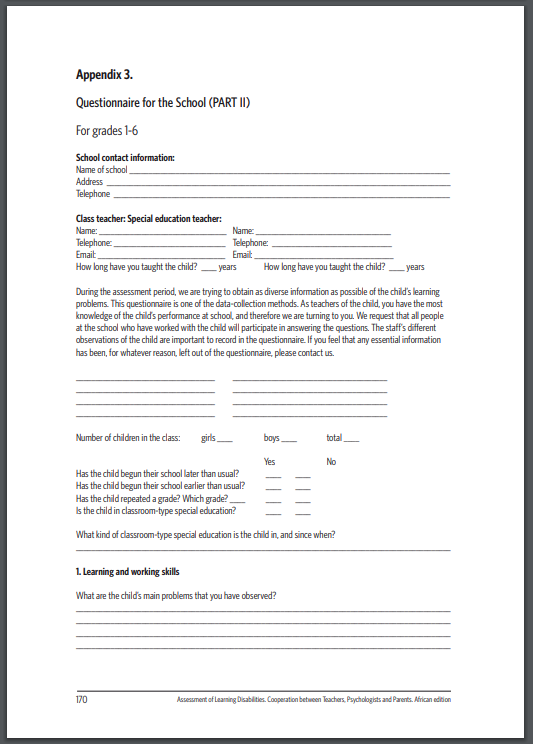

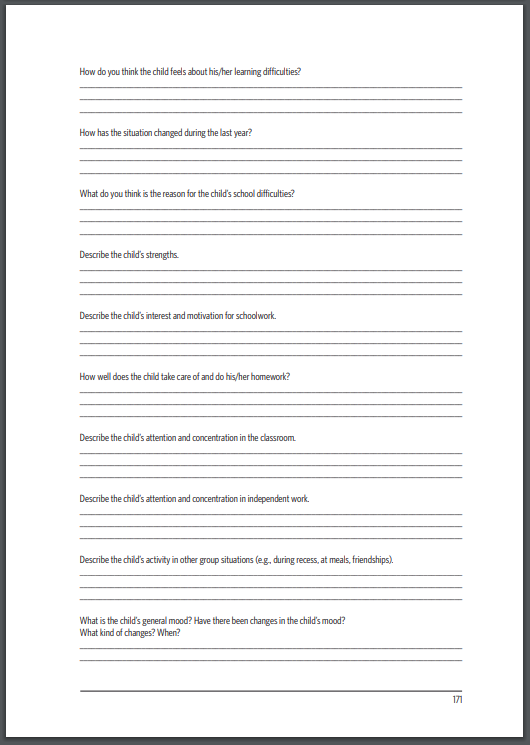

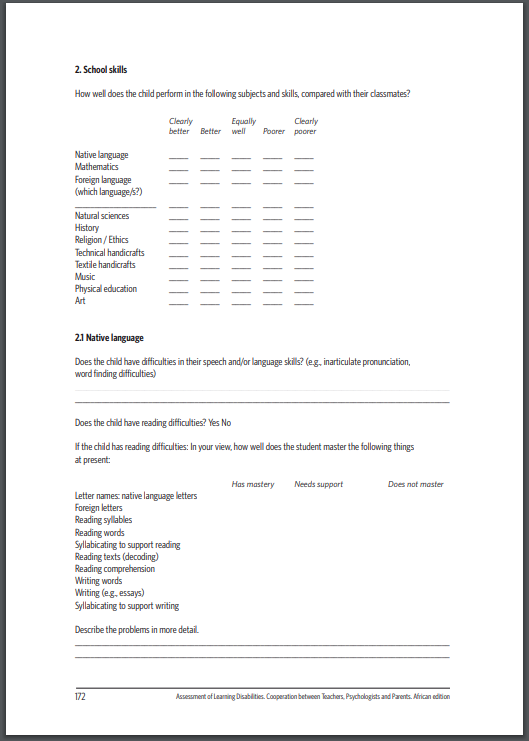

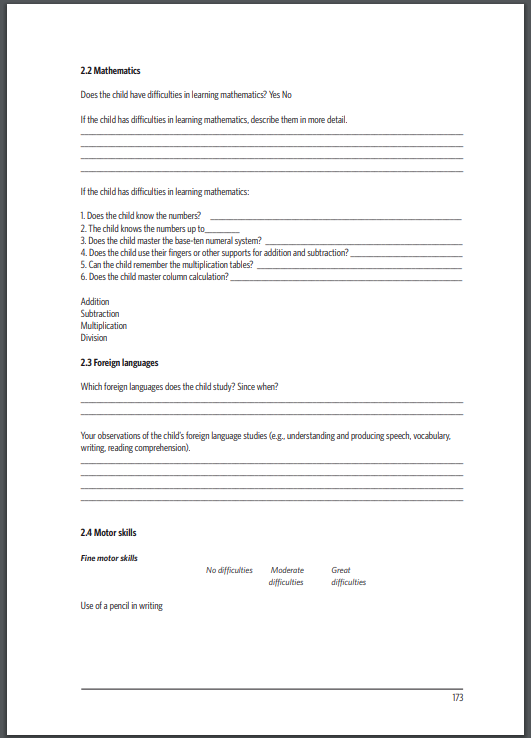

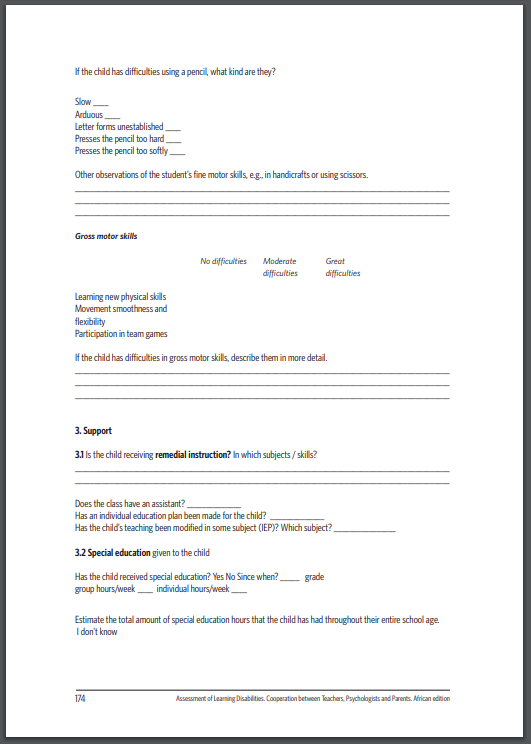

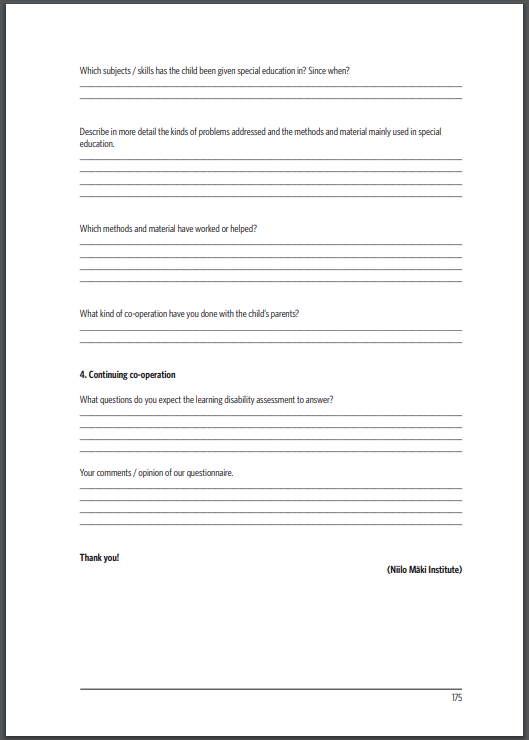

In Appendix 2. there is an example of a form that a school might use when sending a child to a psychologist for learning disability assessment (the form can also be found in the Appendix). In Appendix 3. there is an example of a form that can be sent to a school, from which the psychologist can then map out the child’s learning history, the child’s present situation, and the school’s expectations for the learning disability assessment.

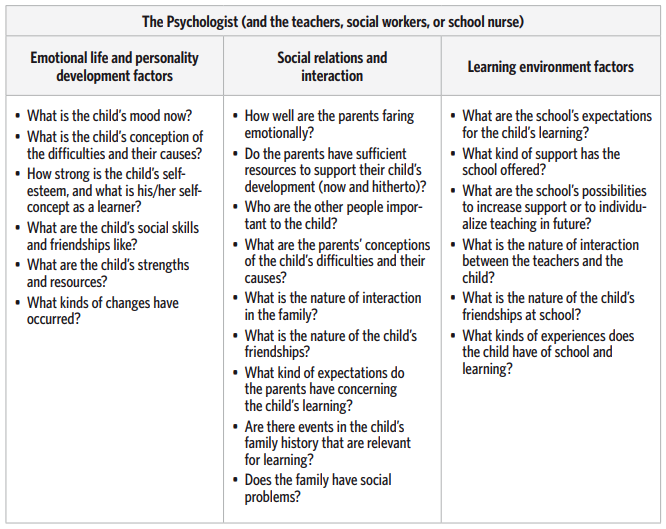

Table 3. Examples of questions for describing the phenotype of the problem