Developing Reading Instruction Plans That Work in Large Classes

Juanita Möller, Pamela February 2021

Table of Contents

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: A Guide for Meaningful Literacy Activities

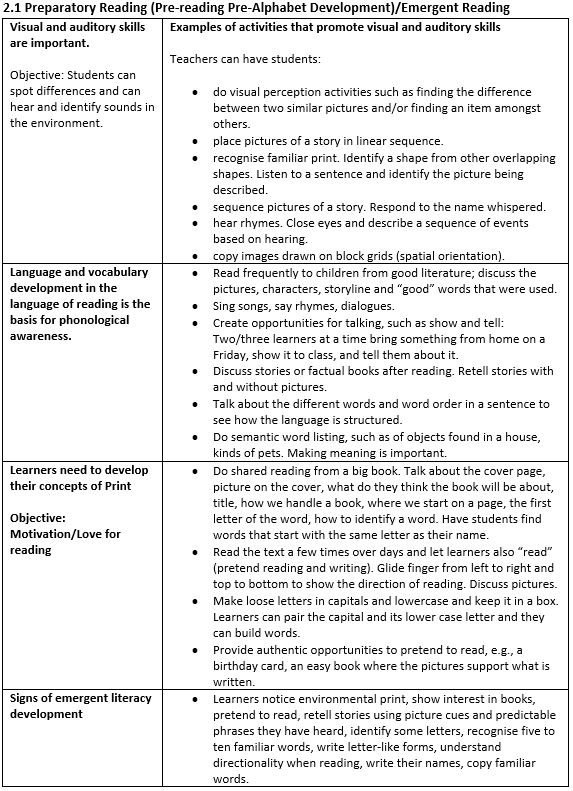

2.1 Preparatory Reading

2.2 Phonological Awareness Activities

2.3 Early Alphabetic Development

Part 3: Launching Literacy Skills

Part 4: Approaches and Activities for Large Groups

Part 1

Introduction

Teachers need to make the best use of learners’ time for them to become skilled readers through sound instructional decisions and active involvement. In most Namibian government schools, teachers are saddled with large numbers of learners who have different needs and experiences with relation to reading proficiency. Teachers need to develop their own plan of action to promote reading in the classroom environment by, for example, making use of group work to attend to learners’ different needs and preferences (Rasinsky & Padak, 2000).

In any large class, there is usually a wide range of literacy skill attainment, and all learners can be involved in the interplay of giving and receiving in the teaching process. Every learner can either be a teacher/example for a struggling reader or be a learner of a more independent reader (Hubbard, 2008). Such a large class can be seen as akin to a multigrade class where there are different skill levels possibly requiring different teaching strategies.

While doing math grouping strategies for a PhD study, I realised that in rotational workstation grouping, more skills can be covered in one well-prepared learning session. When applying this realisation to reading instruction, more skills, such as identifying high-frequency words, sight words, phonics, spelling, writing, word sorts, working with words, exposure to preparatory reading activities (depending on learners’ stage, level of experience, and interaction with literacy events) can be addressed.

Young learners exhibit reading and writing behaviours as a precursor to the acquisition of conventional literacy skills. Many children grow up in an environment where print is valued, but there are also many learners “who begin schooling without having any exposure to reading” (Ramrathan & Mzimela, 2016, p. 1). By applying meaningful group work activities, acceleration, enrichment, and/or learning support strategies can be implemented. Some learners may first need preparatory activities to accelerate print concepts. Preparatory activities include finding differences between two pictures to later differentiate between the different letters and numbers; identifying partial letters; building puzzles; interpreting pictures; matching letters and words; seeing print displayed to develop incidental reading skills, and many others. See Part 2 of this document for more details about preparatory activities.

In this document, various suitable activities and strategies that can be used to promote reading development in large classes are discussed. Teachers can select those strategies that appeal to them and that match their level of experience and interest.

It is a fact that teachers have little time and many subjects to do justice to during the school day. This makes planning and strategising a very important aspect of daily routines. In the junior primary timetable, flexibility is possible. For example, if the teacher devotes one-and- a-half hours to meaningful reading activities one day, the reading aspect can be omitted the next day and that time on the timetable can be allocated to other tasks such as meaningful mathematics knowledge and skills development. There should be no excuse for the poor reading skills of learners. In Namibia, for example, the Ministry of Education prescribes how many hours and minutes should be spent on each subject. Period allocation for each subject is determined by the required time. Teachers may focus on the number of hours and minutes allocated for certain subjects instead of focusing on the subject placement on the timetable to plan sound instruction.

Part 2

A Guide for Teachers on Some Meaningful Literacy Activities

If teachers have an understanding of literacy activities that promote literacy development, it is easier to decide on a group work strategy that will match the literacy activity. Group work strategies with examples, using the activities mentioned below, will be discussed later in this document.

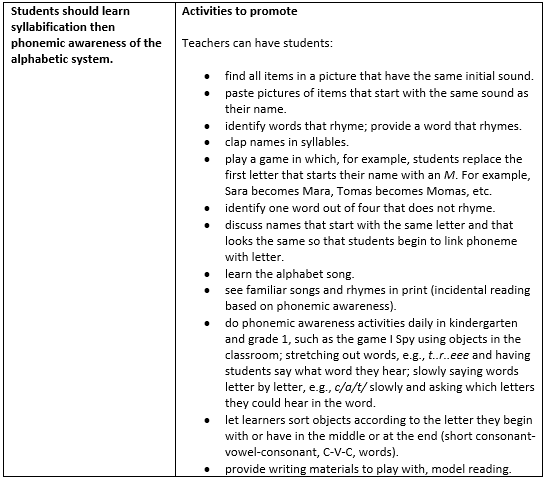

2.2 Phonological Awareness Development

PHONEME AWARENESS; The purpose is to hear, identify, and manipulate individual speech sounds; Phonemic awareness may require various skills, such as, e.g., identifying rhyme, initial sounds, ending sounds, middle sounds, blending sounds, substituting sounds, segmenting compound words, segmenting the sounds that make up a short word. PHONOLOGICAL SKILLS may include, e.g., alliteration; segmenting words in a sentence, counting the number of words in a sentence;; onset-rime endings to make other words containing the same pattern.

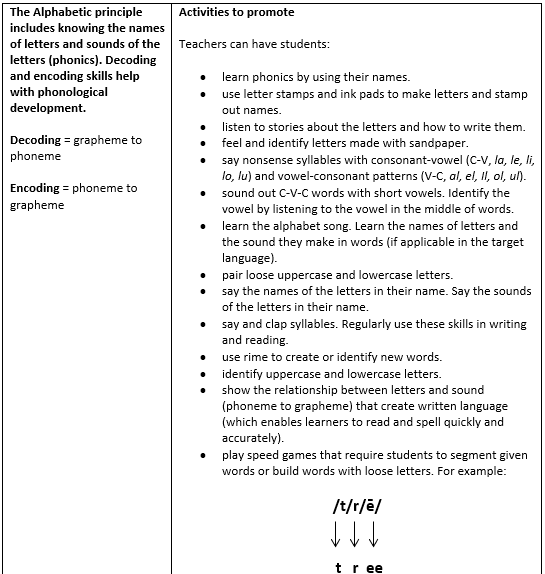

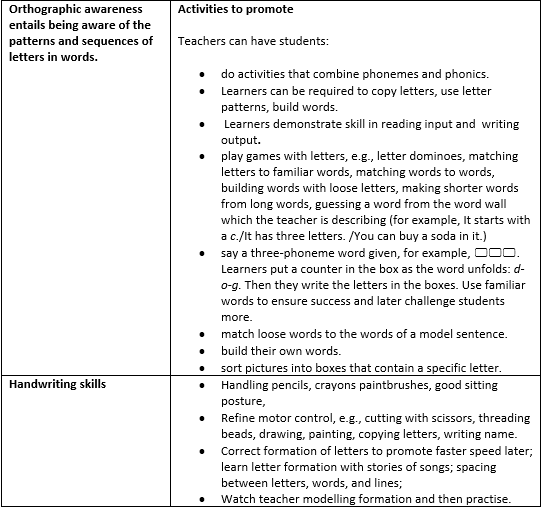

2.3 Early Alphabetic Development

Learners are required to do decoding using phonics, finding shorter words in a long word, do syllabification, read certain words on sight, use rime patterns to write new words.

Part 3

Launching Literacy Skills: Some Ideas to Trigger Creativity

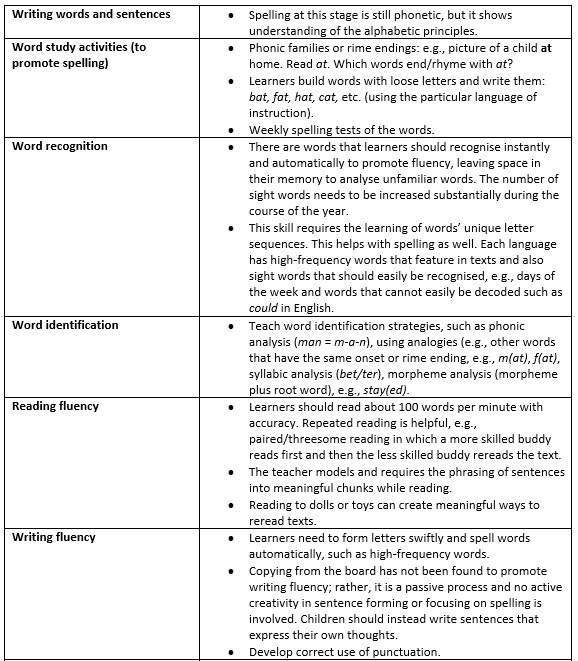

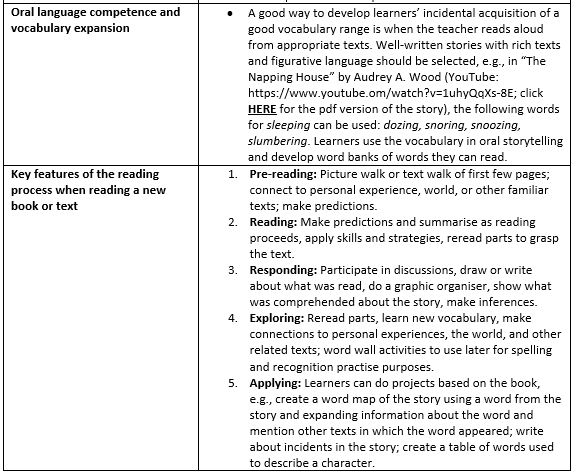

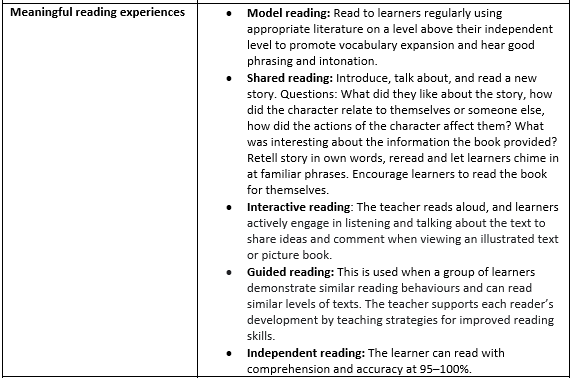

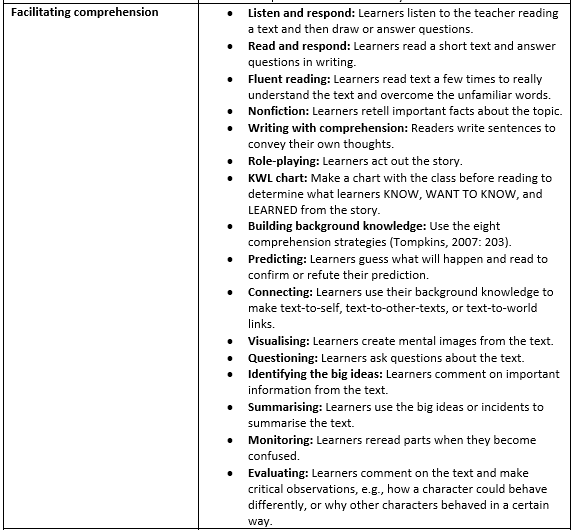

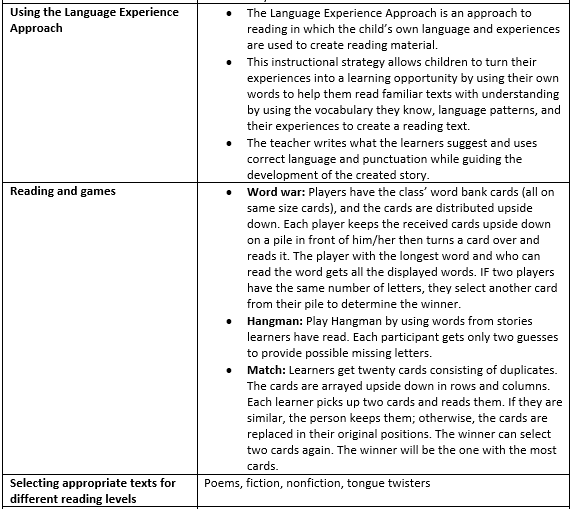

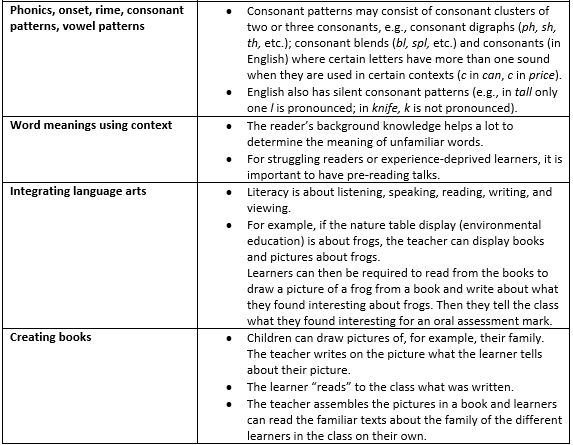

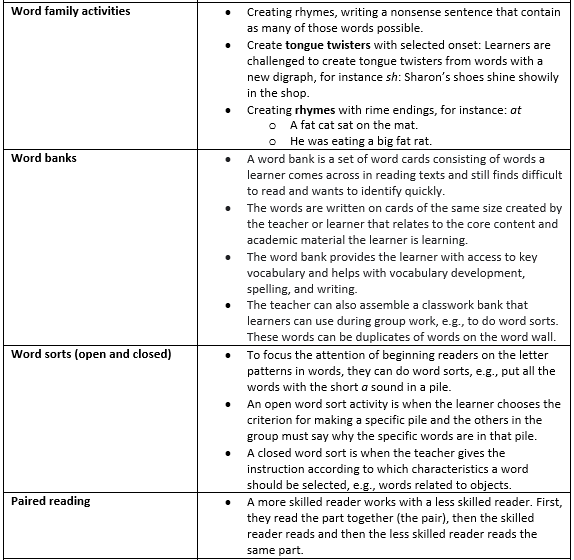

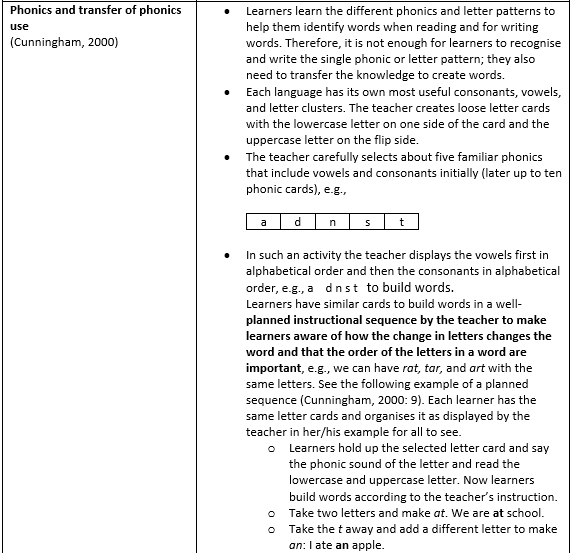

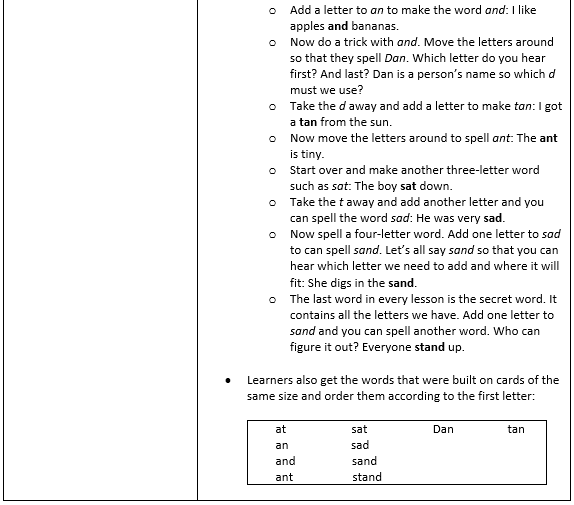

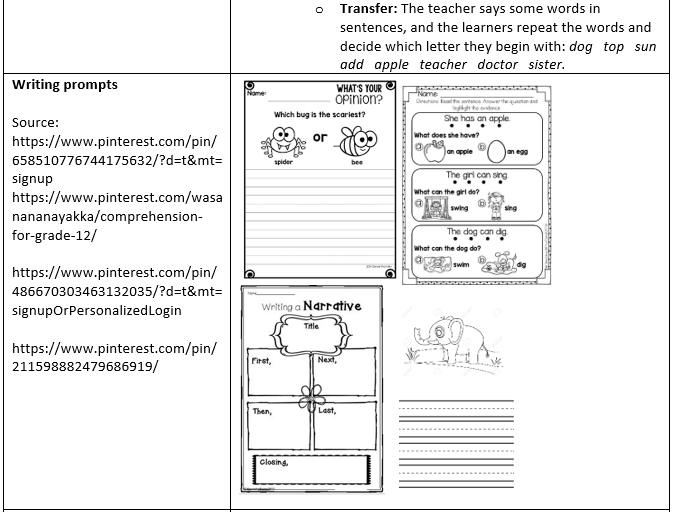

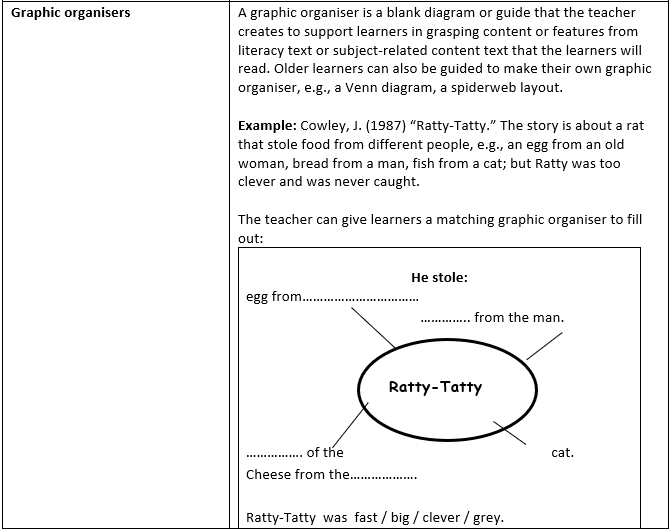

There are certain strategies that a teacher can use to promote literacy development in young learners. In the following table, we have assembled ideas from several sources

(Tompkins, 2007) (Wilson, Hall, Leu, & Kinzer, 2001) (Vacca et al., 2008) (Rasinsky & Padak, 2000).

Part 4

Approaches and Activities to Help a Large Group of Learners Develop Successful Reading Skills

Group Work

Group work is meaningful to help teachers attend to learners’ different needs and preferences (Rasinsky & Padak, 2000). In a large class, it becomes very challenging to achieve effective individual learner growth. A teacher who allows learners to engage in group work needs to prepare suitable teaching and learning materials for the groups. In light of limited resources in many schools, the group work examples that follow contain little photocopying and rather focus on materials teachers can make; moreover, if carefully organised and stored after use, they can be utilised repeatedly in different activities, e.g., loose letters for learners and high-frequency words on flashcards written on the insides of discarded cereal boxes. These activities should enrich and promote literacy knowledge and skills.

Note: Although the examples for group work activities are predominantly for English, teachers using other mediums of instruction can adapt the activities to suit that particular language.

As there are varying degrees of literacy development in learners, teachers need to build upon literacy concepts that need strengthening or have been acquired. All elements of literacy development develop interactively and supportively: listening, speaking, reading, writing, viewing, and illustrating (Antonacci & O’Callaghan, 2004). Learners take different paths to master literacy, and teachers need to plan literacy development according to their strengths and needs (Antonacci & O’Callaghan, 2004).

In large classes, e.g., 45–60 or more learners, grouping becomes necessary to focus on the identification of literacy needs of individual learners while they are in a smaller group.

Tompkins (2007) recommends that successful group work requires the establishment of a cooperative classroom community so that learners take responsibility for learning and use opportunities for meaningful engagement, self-monitoring, and self-assessment. As classroom manager, the teacher should instil organisational routines for the first two weeks of the year to make the classroom setup predictable and promote cooperative learning. The teacher needs to clearly explain and let learners practise what they need to do, e.g. moving into groups, workstation procedures, handing out and submitting work, how to participate in classroom activities, raising a hand to talk, demonstrating positive behaviour towards others, how paired reading will work, how working in groups will work. The teacher models how learners need to interact with each other, how to respond and respect others. They should praise learners for positive behaviour and show appreciation for expected behaviour beforehand. During the course of the year, the teacher reinforces classroom routines and establishes additional ones as the literacy skills of learners advance. Learners need to learn to become examples of “positive pals” for others in and out of the classroom.

The teacher can make use of different methods to establish groups (Joubert, 2008), e.g., proximity, birthdays in the same month, needs, practical grouping to use space optimally, paired groups of a more successful reader and a less competent reader, peer teaching groups, similar needs groups. Groups should not be static but change according to learners’ development.

To make cooperative group work function, each member of a group needs to have a role, and the group activities need to be interesting and meaningful, e.g., play-to-learn activities. The roles should be changed regularly. Groups should preferably consist of no more than six learners per group; however, in large classes too many groups may be counterproductive. Below are some possible roles that can be allocated, written on cards, and displayed on each person:

- leader and “teacher” who ensures the task is executed with minimal noise

- motivator and noise-level commander

- scribe

- spokesperson

- fetcher

- tidy-upper

- vocabulary collector and meaning finder

- word wall; word poster

- handing-out person, e.g., self-assessment sheets, activity sheets

- timekeeper

Group Work Setups

Group work can sound noisy for outsiders who might think the teacher has no control, but this should not deter teachers from doing it because learners learn a lot from peers (and little ones cannot be expected to sit like little robots!) It should be “educational noise” in which learners learn to interact meaningfully with others by following the instructions and restrictions for group work and taking on the group member roles. The teacher can allocate, for example, tokens for good group behaviour. After earning five tokens, a group can exchange it for a prize, such as having a soft toy sit with them for the whole day or having their photos displayed in a special place in class.

It is important for the teacher to set a timer to ring when the allocated time for group work expires, e.g., after twenty minutes. The teacher might allocate up to an hour or bit longer to have enough time if students are doing rotational activities.

Whole class teaching followed by individual work

Example: The teacher gives a mini-lesson on the use of punctuation for the full stop/period and for new sentences starting with a capital/uppercase letter.

Learners identify sentences in a given page of text and count how many sentences they find on the page. They then copy one sentence into their book.

OR

The class, together with the teacher, creates a story about two objects, e.g., a pencil and an eraser, using the Language Experience Approach. The story is written on a sheet of blank newspaper or sheets of A4 paper. The class rereads its story.

The next day the learners can write the sentence they like best and illustrate it.

Whole class teaching followed by breakaway groups

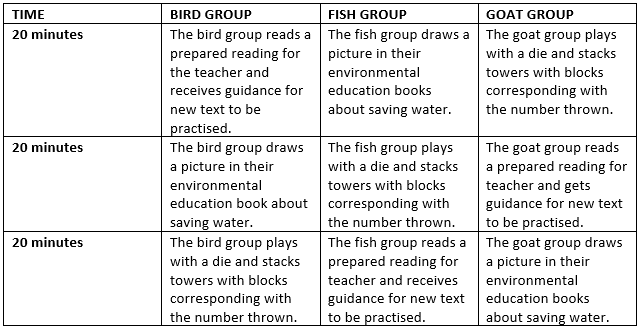

The class can be organised into three groups for this strategy. One group of learners will have acquired strong literacy skills (the fish group), the second group will display beginning literacy skills (the bird group), and the third group (the goat group) will still need repetition and more experience for literacy development to take off.

The teacher teaches a strategy to the whole class, then two groups break away as instructed to do an assignment while the other group stays with the teacher to do either reinforcement or enrichment, depending on the teacher’s planning.

Example: The teacher flashes high-frequency words for the learners to read in chorus intermingled with familiar phonics cards. The fish group then breaks away and has to circle all words they can immediately identify on a piece of the given text. They file the page in their flip files and compare it with others in the group who could read the most.

The remaining two groups each get a word or letter card, and each learner has to show the card to the group while reading what is on the card. Then the bird group breaks away, and they have to circle ten words in the given text that they can easily read. They then compare with friends in the group which word was the most popular. They file the page in their flip file.

The goat group remains with the teacher to play a game, e.g., the words are set up like the rungs of a ladder and individual children see how high they can climb on the ladder by reading the words until they take too long to identify a word. Then another learner gets a chance to climb the ladder. The winner is the learner who climbs the highest.

Subject-alternating strategy

The teacher can use an hour with this setup. Learners will not get tired so easily as they will be refreshed when getting a new task activity after twenty minutes.

The class can be divided into the groups (e.g., fish, birds, and goats).

After groups have participated in the various activities, the teacher harmonises the class as a whole again by, for example, letting them sing a song or say a rhyme.

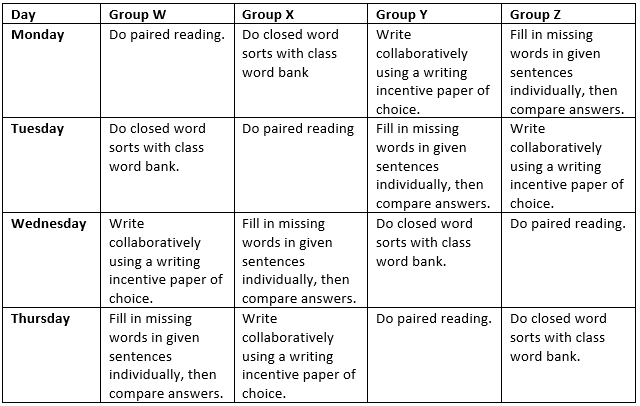

Groupings for cooperative tasks

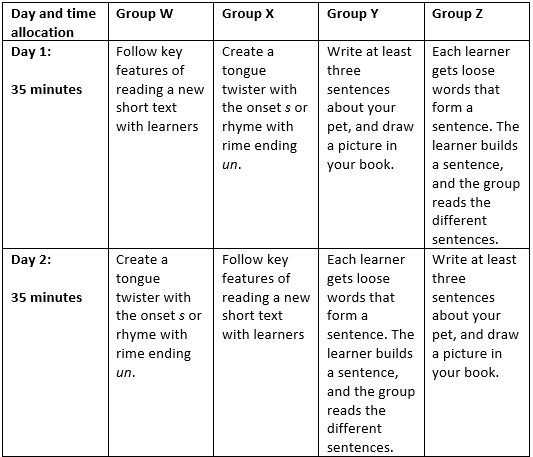

Over the course of four days (e.g., Monday to Thursday), the teacher can give learners literacy experience tasks where the group cooperates for the duration of the period. Over the four days, each group gets to do all the different activities, and on the fifth day (e.g., Friday), there can be an assessment of what was done.

Example:

Rotational groupings for small group instruction

For small group instruction and with the purpose in mind of strengthening or enhancing reading proficiency, a smaller group needs to be with the teacher during each rotation. Many small groups will be too difficult for the teacher to manage on a single day; therefore, this strategy may have a duration of three days or more so that the teacher has the opportunity to pay attention to each individual. For example, the rotations could take place over four days with four groups.

At the start of the literacy period, the teacher organises which group should do what for the duration of the period, makes sure each leader knows what the group has to do, and hands out learning materials the group will use.

Individual work on tasks

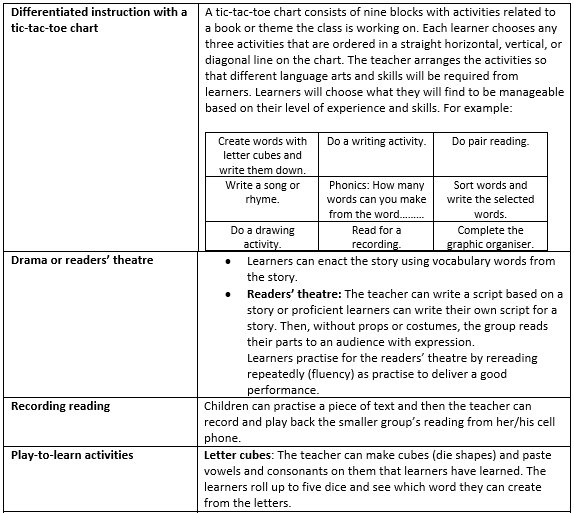

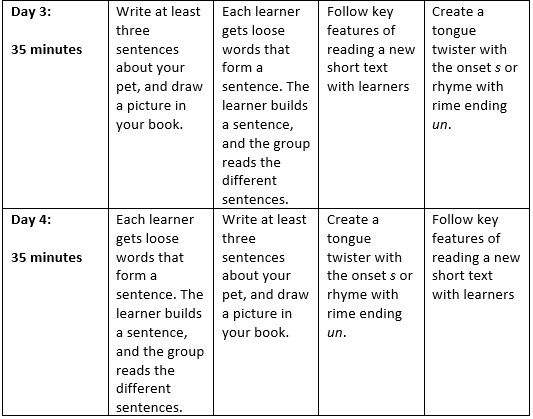

The teacher might have tic-tac-toe activities on a sheet of blank newspaper, and the learners choose three activities and do them.

Example: Four-block tic-tac-toe for kindergarten learners. The teacher can use guiding pictures to help children remember the instruction that was read.

https://www.clipartkey.com/view/woxho_childrens-drawing-clip-art-cartoon-child-drawing/

https://za.pinterest.com/pin/534521049519104632/

http://getdrawings.com/get-drawing#picture-of-a-person-drawing-36.jpg

https://www.safecom.org.au/child-detention.htm

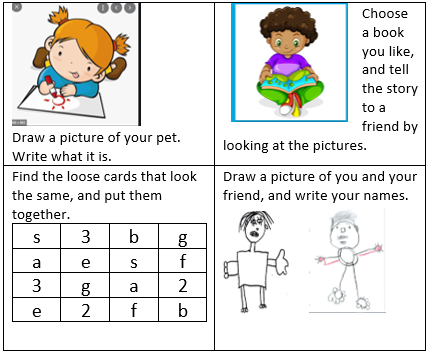

Workstation technique

The teacher can lay out activities at four workstations before school. When school starts, the children receive clear instructions of what to do at each station while walking with the teacher to each station (The group leader can come and verify later if a group forgets.) The teacher rings a bell after fifteen minutes, and the groups move to a new station in clockwise rotation. Groups can be formed with letters, e.g., W, X, Y, Z.

References

Antonacci, P. A., & O’Callaghan, C. M. (2004). Portraits of literacy development. Australia: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Cunningham, P. (2000). Systematic Sequential phonics they use. North Carolina: Carson-Dellosa Publishing Company Inc.

Hubbard, H. (2008). Teaching Math in the multigrade classroom. Adventist Education. Retrieved from http://circle.adventist.org/files/CD2008/CD1/jae/en/jae199456034103.pdf

Joubert, I. (. (2008). Literacy in the Foundation Phase. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik.

McLauchlin, M., & Fisher, L. (2005). Research-Based reading lessons for K-3. New York: Scholastic.

Ramrathan, L., & Mzimela, J. (2016). Teaching reading in a multigrade class: Teacher adaptive skills and agency in teaching across grade R and grade 1. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 6 (2). doi:10.4102

Rasinsky, T., & Padak, N. (2000). Effective Reading Strategies. Teaching children who find reading difficult. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Roe, B., Smith, S., & Burns, P. (2009). Teaching Reading in today’s Elementary Schools. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Tompkins, G. E. (2007). Literacy for the 21st century: Teaching Reading and Writing in Pre-Kindergarten through Grade 4. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Vacca, J., Vacca, R., Gove, M., Burkey, L., Lenhart, L., & McKeon, C. (2008). Reading and learning to read. New York: Pearson.

Wilson, R., Hall, M. A., Leu, D., & Kinzer, C. (2001). Phonics, Phonemic awareness and word analysis for teachers: An interactive tutorial. 7th Ed. New Jersey: Merril Prentice Hall.